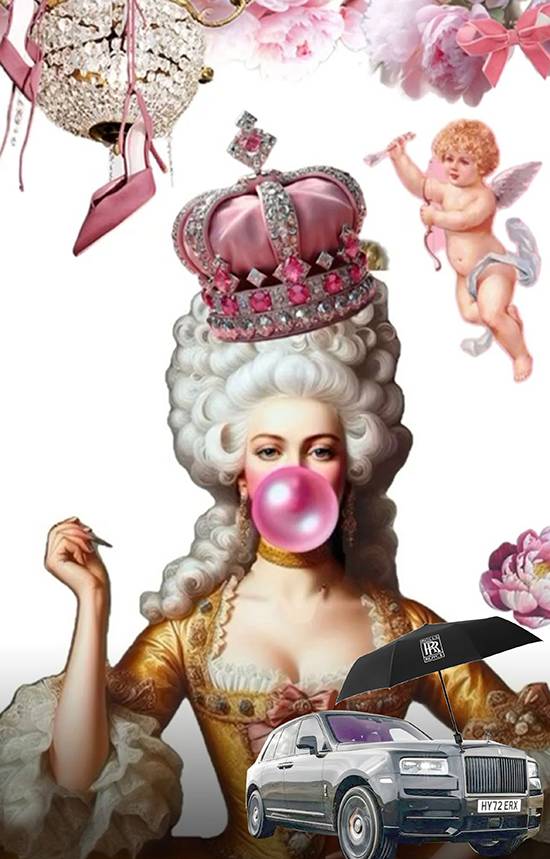

Is revolution, like Marie Antoinette, in season?

Let them eat Rolls-Royce

In Paris, the whispers began not from the catwalks of haute couture but from the fields and the highways. They spoke of a new and elegant discontent, a feeling that had little to do with hemlines and everything to do with the guillotine. For months now, French farmers have blockaded city centers. Their protests against the rollback of a diesel tax subsidy and the crush of foreign competition are a furious counterpoint to the imperturbable splendor of the Grand Palais.

In New York, the streets of Manhattan, once a theater of endless possibility, now heave under a palpable weight. The tension, the clashes with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, the shouts of protest against a federal crackdown on sanctuary policies are a discordant hum in the city’s song. It is, as the fashion editors would say, a time of paradox.

That dissonance grows sharper with the relentless return of Marie Antoinette to the very center of fashion and pop culture this season. The last queen of France before the French Revolution is everywhere at once. She lives in the BBC historical fiction series Marie Antoinette, renewed for a third and final season, and in a Manolo Blahnik-backed exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, running until March 22, 2026. She is Miley Cyrus on the cover of Perfect Magazine’s August 2025 issue. She is model Lily Chapmann, styled as the queen, on the cover of Tatler UK’s September 2025 issue. She is Jacquemus staging Le Paysan at the Palace of Versailles to unveil his spring/summer 2026 collection, revisiting the extravagance John Galliano immortalized for Dior in 2001.

The image of the queen of excess has not just been resurrected, it has been recast as a patron saint of our modern malaise. Her tragic glamour, once a historical footnote, is now a lens through which we view our own turbulent moment. Her sense of opulence feels less like a cautionary tale than a prophecy, as if runway shows and covers were divining the coming storm.

And the storm is everywhere.

It is in Manila, where heavy rains expose not only the city’s flawed infrastructure but also the rot of a corruption scandal over ghost projects and kickbacks in flood control funds. It is in the homes of the poor, submerged for the third time this year, while the alleged kickbacks fill the pockets of a select few. It is in Nepal, where youth-led protests, triggered by a social media ban, have spiraled into riots, with furious young people burning government buildings as they rail against politicians’ children, whose ostentatious lives are documented for the world on TikTok. It is in Indonesia, where protests erupted after parliamentarians granted themselves a generous housing allowance, and rioters looted the very homes of those who voted for it.

The world today, much like that final moment in the court of Louis XVI, seems to be approaching a breaking point. It is a moment when the grand gestures of the powerful, from a lavish allowance to a non-existent flood wall, feel like taunts, and the silence of privilege is deafening. The anger of the people is no longer a whisper but a scream. The guillotine, never just a tool of execution, became the symbol of a society that had lost its balance.

To the legendary Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, the best clothes are a prophecy. “Fashion is part of the daily air and it changes all the time, with all the events. You can even see the approaching of a revolution in clothes,” she said.

She was right. What is the return of Marie Antoinette’s aesthetic if not a premonition? It is the elegance before the fall, the final glorious bloom before the rot sets in. Her pastel colors and extravagant silhouettes are less artifacts than warning shots across the bow for a society celebrating excess while its foundations crumble.

This is the great irony of our time. We worship the symbol of an elegant, self-destructive era precisely as our own world teeters on the brink. We are drawn to the image of Marie Antoinette not because we want to behead her, but because we secretly long to be her, if only for a moment. We want the thrill of her gowns and her powdered wigs, the careless abandon of her extravagant life, because the alternative is to confront the hard truths of our own impending revolutions. We see the pleasure, and we try to forget the tragedy.

But the tragedy is the point. Marie Antoinette is the ghost that haunts every runway and every riot-filled street, a reminder that the chasm between the very rich and the very poor cannot be covered with blush or hidden under a towering wig. She is a mirror. In her reflection, we see ourselves, poised at a dangerous and beautiful precipice, hoping our cakes do not run out before the storm begins.