Gregorio C. Brillantes, maybe the last of the mohicans

Philippine English fiction writer Greg Brillantes died at the age of 92 on a Friday, the last weekend of September, as a severe tropical storm was heading straight to the central islands of the archipelago.

His second daughter, Cecilia, perhaps named after the patron saint of music, was surely coming home after many years based stateside.

"Chi," as she was called, was one of my students in English I at UP Manila four decades ago. She was part of a memorable, rowdy block of occupational therapy majors. Her father, often mentioned in class, was the renowned author of Faith, Love, Time, and Dr. Lazaro. That story, a staple in college syllabi introducing students to literature, tells the tale of a country doctor who learns a vital lesson about faith from his own son.

It wasn’t until after the first EDSA revolution that I got to work closely with Greg B., as he had once written his name in my pocket directory (***9507). He was an editorial consultant for Midweek magazine for six years, and I was among the staff writers. Of course, I'd read more of his work, aside from the aforementioned piece. There was The Distance to Andromeda, which made you never look at the night sky the same way again. And The Cries of Children on an April Afternoon in the Year 1957, an ode to adolescence in the province of Tarlac, although written in prose.

Greg also edited The Manila Review, a martial law era literary journal that came out more or less quarterly, where I first read Erwin Castillo’s The Watch of La Diane, as well as a sheaf of poems by the teenage poet Diana Gamalinda, who drowned in Vigan in 1978. The Review was also where I saw mind-blowing illustrations by the likes of Red Mansueto.

In Midweek, the hours were lax—so long as the issue was put to bed on at least a weekly basis. Greg was usually behind his desk in the afternoons, wrestling with a copy of the writers and columnists, the blue pencil eventually rendering the poorly edited copy like a Rorschach test, which made you pity the encoder who had to manually put in all the corrections and transpositions in the rewritten article.

He was hard of hearing and often cupped a hand to his ear when he struggled to catch what you were saying. Also, you should have seen him when he was deep at work, sometimes shaking his head and muttering the ritual “tsk, tsk, tsk,” looking at copy from a certain angle so light would fall on it the right way, before applying his editing pen as if he were doodling or doing a spot cartoon.

After hours, there was time for some beer, sometimes in the old gutted building beside the office on A. Roces Avenue, Quezon City, or else a short drive or taxi ride away to Davao Inihaw on Timog, where the inihaw na panga and sisig were quite the treat after not such a hard day’s work. It was at Midweek where we first developed a sort of journalist routine, learned the ropes of the trade, out of town coverage, and tightrope deadlines, especially since the magazine’s editor-in-chief was Pete Lacaba, who taught us all the basics of days of disquiet, nights of rage.

Greg drove an old model Mercedes-Benz that might have seen better days, the backseat filled with books he would occasionally give away to young writers, and near the dashboard, a pile of cassettes that included Ol’ Blue Eyes.

Before Midweek closed down with the exit of the first Aquino administration, Greg had gone on a central American sojourn following the death of his mom, which coincided with political upheavals in Nicaragua and other parts of the region, and the essays written at the time later formed the main section of a book of essays, traversing most of the continent by bus, train or foot, and recording his adventures in drafts written in long hand.

After Midweek, it was on to Graphic magazine, where Pete already was, as well as national artist Nick Joaquin, the Cabangon Chua publication along Pasong Tamo and dela Rosa that spawned its own counterculture. Greg also had a regular column in the Times Journal, the title of which I forget, but it was in the manner of Nick’s “Small beer.”

At the turn of the millennium I asked Greg to contribute an essay for a special supplement of The Philippine STAR, sort of like to beat the projected 2K bug, and he delivered in spades, recalling his fledgling years at the Ateneo along Padre Faura just after the Pacific War, as an FOB (fresh off the bus or Benz) provinciano from Tarlac, and his corps commander at ROTC was a fellow named Max Soliven, who was described unflatteringly as strutting around with his sword, or words to that effect.

We met at Solidaridad, Sionil Jose’s bookshop on Faura, so I could hand him his writer’s fee in early 2000. After much shouting and repeated phrases on the phone to set the appointment, he was, as usual, in his element among books, as calm as any browser. He invited me to lunch at a nearby eatery, on the second floor of which he said there used to be a girls’ dorm, where he and his batchmates at Ateneo visited on weekends, maybe with an impromptu serenade in mind.

In the 2010s, I saw less of him, except for a Midweek reunion at Teacher’s Village in the house of one of the magazine’s staff writers, Tezza Parel. I had brought a bottle of Capt. Morgan spiced rum, which he was hard put to part with until I drove him and other staff home to Sta. Mesa Heights. Although the dog Juanito is no longer around, he wouldn’t let us leave without giving us a couple of books, however, yet unread somewhere in the apartment.

Or else in New Manila at the house of fellow writer Ben Bautista, dinners with Pete and Krip Yuson washed down with single malt while in the lanai, works of Bautista’s bosom buddy Chabet kept watch over us.

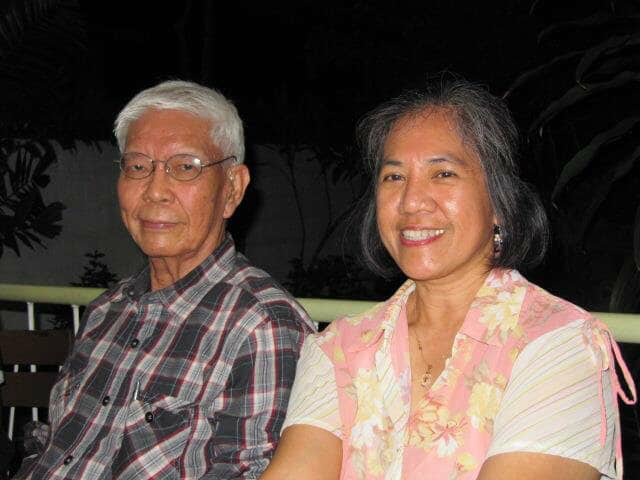

In Baguio, of course, I bought his collected short stories to shore up a weather-beaten, dog-eared copy of The Apollo Centennial, which still sits by my bedside. Now, Chi is finally home from Houston to join her two sisters and mom. The distance to Sta. Mesa Heights is hardly measured by the words of a great writer who taught us much.