The polarities of Don Bryan Bunag and Isko Andrade

At Art Fair Philippines, on view to the public from Feb. 6-8 at Circuit Corporate One Center at The Circuit, Makati, two exhibitions propose distinct yet resonant modes of inhabiting the world through painting. Art Cube’s presentation, “Inhabitants,” a solo show of Don Bryan Bunag, confronts the viewer with environments that feel monumental, awe-inspiring, and movingly mysterious. In contrast, Isko Andrade’s “After Solace,” this time under Art Verité, offers an intimacy of vision shaped by touch, memory, and quiet repetition.

In “Inhabitants,“ Bunag extends painting toward the condition of an inner environment—one that feels uncannily close yet remains fundamentally unreachable. Inflected by Immanuel Kant's thought of “inner sense,” the means by which we perceive and represent the various states of the mind, the works situate the viewer before spaces that resemble thresholds, cosmic events, and scenes on the verge of transformation: domains that seem to recognize us, even as they seem estranged.

Working within a restrained monochrome tempered by bluish inflections, Bunag summons a visual language of sacred geometries, portals, structural repetitions, and quiet intimations of the void. The scale of the canvases amplifies this encounter, drawing the body into a direct confrontation with form and absence, surface and depth. These are not images to be glanced at but fields to be entered—if only imaginatively —through the artist’s unwavering and exacting vision.

From the impenetrable opacity of the triptych “God of the Gaps” to the hovering incision of “Omnipresence,” Bunag translates mystery into the living matter of paint. Fabrics and threads are integrated into the canvas, producing textures that feel embedded rather than applied, as though signals were being transmitted from beneath the skin of the work. These tactile interruptions suggest coded messages—traces of an underlying order, or perhaps of its breakdown—hinting at realities that exceed what can be fully seen or named.

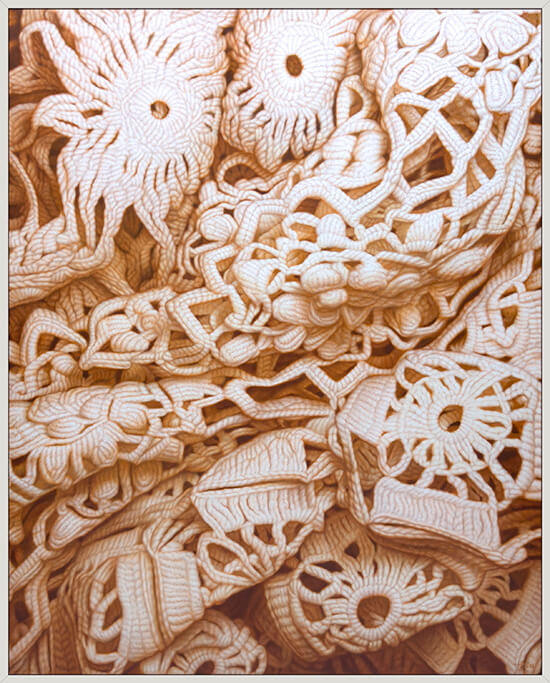

Meanwhile, in “After Solace,” Andrade invites us into a mode of seeing that is intimate and unhurried, drawing the world close enough for its smallest articulations to matter. The exhibition asks us to linger on what is usually overlooked—to attend to the quiet labor and minute decisions that constitute an embroidery, and by extension, an image.

Through a painstaking method that privileges patience over spectacle, Andrade renders not only threads and patterns but the subtle negotiations between light and shadow as they settle on material. Depth emerges gradually, not through illusion alone but through an accumulated attentiveness, where each detail is allowed to surface in its own time. What is depicted is less an object than a condition of looking — slow, deliberate, and exacting.

All the works in the exhibition return to a single motif: the interlocking threads of embroidery. The subject is immediately recognizable to those who grew up alongside older generations of women who passed the hours stitching—an activity at once domestic, meditative, and quietly sustaining. In revisiting this familiar object, Andrade reframes it as a site of memory and continuity, where repetition becomes a form of care.

For Andrade, these works offer a form of calm. By conveying the tactile softness of the material, he allows the viewer not only to see but to feel the image—visually registering texture, weight, and warmth. “After Solace” becomes an invitation to share in that quietude, to experience painting as a space where attention itself becomes restorative.

Together, the two exhibitions form a charged dialogue between weight and lightness, awe and care—reminding us that painting can encompass both the vastness of speculative worlds and the restorative calm of the familiar, each recalibrating how we see, feel, and inhabit our own.