The curtain rises again: Toff de Venecia's next act

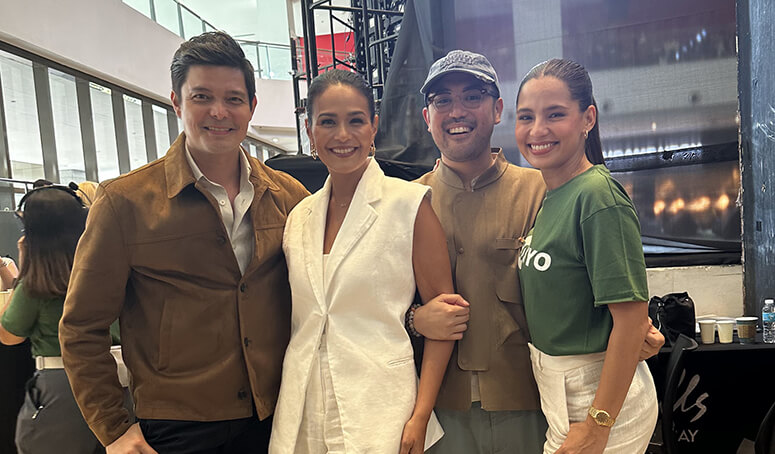

On the eve of a departure that felt like both an ending and a beginning, I ran into Toff de Venecia. Side Show, which closed at the Black Box Theater at Circuit Makati on Sunday, was his last production before London, his swan song before he leaves to pursue post-graduate studies. “Whatever I learn in my master’s, I’m determined to apply when I come back to Manila, whether in the arts, public service, or another field entirely,” he said.

When I first met Toff, I thought of theater not as a stage, not as lights and curtains, but as a kind of restlessness. He has the look of someone who can never quite sit still, though his chill exterior might suggest otherwise. There is always a plan, a project, a possibility. When he speaks, it feels less like a statement and more like an invitation, the way a director coaxes a performance out of his cast.

The name he carries is political. The weight of being a de Venecia—the son of a five-time Speaker of the House, Jose de Venecia Jr., and a former congresswoman, Gina de Venecia—in Pangasinan could have kept him tethered to bureaucracy, the grind of committee work, the scripted lines of Congress. Yet Toff has always been a producer at heart, staging ideas rather than speeches, with a vision that stretched past the proscenium. His district became his sandbox, and from it emerged an experiment that enriched the landscape of Philippine theater.

In 2014, a couple of years before the curtain rose on his political career, Toff founded The Sandbox Collective out of a desire to create work that mattered. He spoke of it as a platform for contemporary, cutting-edge productions, but what struck me most was the sheer audacity of its beginning. At a time when commercial theater in Manila was playing it safe with familiar blockbusters, he championed productions that felt like a brave insurgency, each story a provocation. I remember sitting in its inaugural production of Dani Girl and sensing electricity in the air, a collective understanding that we were witnessing something raw and new.

“I’m very interested in doing work that is not only entertaining, but also socially relevant,” Toff once told me, and it is a line that has stayed with me. It explains why Side Show feels like such a fitting farewell. He transformed the musical, based on the lives of conjoined twins Daisy and Violet Hilton, into a metaphor that went beyond spectacle. It was a story of otherness, and a poignant commentary on our politics, where a longing for belonging is negotiated in the harsh glare of the spotlight.

Watching Side Show, I felt as though Toff was staging his own exit. Not a final bow, but a transition. After a decade in Congress, he is leaving for London to pursue a master’s degree in Public Administration in Innovation, Public Policy, and Public Value. The phrasing of that degree, long as it is, reads like an extension of his creative agenda. He has always sought to innovate, to test the limits of what public service might mean, to explore value beyond the measurable.

It is tempting to see Toff’s trajectory as two parallel tracks, politics and theater, one demanding pragmatism, the other indulging imagination. But to him, they have always been entwined. “Each deeply informs the other,” he said. “My work in public service influences the kind of theater I create. In fact, theater becomes an extension of my advocacy work. My work in the theater and the creative industries lights the fire behind my advocacy of championing arts and creativity in the public sector.”

This entwining explains the unusual legacy the 38-year-old leaves behind. There are the laws, of course—the Creative Industries Development Act (2022), the Eddie Garcia Law (2024), the Cultural Mapping Law (2023). Each was, in his words, a leap in the dark. It is a way of thinking he has always looked to for guidance, one that finds an echo in the wisdom of American dancer and choreographer Agnes de Mille. “As artists, we don’t know,” she confessed. “We just guess. We may be wrong, but we take leap after leap in the dark.” He said it was a philosophy he started to embrace when he worked on Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel for Repertory Philippines.

But there is also the body of work with Sandbox, 11 years of advocacy-driven theater, productions that pushed audiences to feel more, think harder, connect deeper by humanizing and making accessible such heavy subjects and complex themes as a child’s perspective on terminal illness in Dani Girl, bi-polar disorder in Next to Normal, obsessive-compulsive disorder in The Boy in the Bathroom, and chronic depression and suicidal impulses in Every Brilliant Thing. Side Show closed the loop with its bravery.

Behind these public-facing achievements lies a humbler, unglamorous discipline. “Even with creative output that can be perceived as sexy, there is a lot of unsexy,” he admitted. “Behind every landmark piece of legislation or every meaningful theater production, there is time spent rolling up your sleeves, brainstorming, and then barnstorming or fighting to be heard, working within institutions and systems that are not always receptive to innovation, disruption, or change. Nevertheless, you soldier on.” He cites New York Shakespeare Festival founder Joseph Papp, who spoke of “revolutions in small spaces.” That phrase, too, could define Toff’s career, whether in the rehearsal hall or the committee room.

Now, as he prepares to leave, there is both trepidation and resolve. “It’s a mix,” he said of his emotions. “I’m nervous-excited-anxious, feeling a bit insecure—What if I’m not good enough? For this new chapter, I’ll just have to hold space for myself and, with hope, rise to the occasion. Goodbyes are always sad, but with theater, I know it’s definitely a see-you-later. For now, it’s time to turn a page.”

And so it is. Toff’s next act begins not in Manila, but in London, where he will be, as he puts it, “a small fish in a big pond.” Yet those of us who have seen him wear his two hats, both as creative and as congressman, know that he has never been afraid of the leap. He leaves us with laws, with plays, with a conviction that politics can be art and that art can be politics. He leaves us with the image of Daisy and Violet Hilton singing in unison, two bodies, one voice, bound together yet striving for freedom.

I think of Toff in that light, two halves that do not cancel each other but enrich the whole. A politician who makes theater, a theater artist who makes policy. And like the best shows, his life so far ends not with closure but with anticipation. Curtain call, then curtain rise.