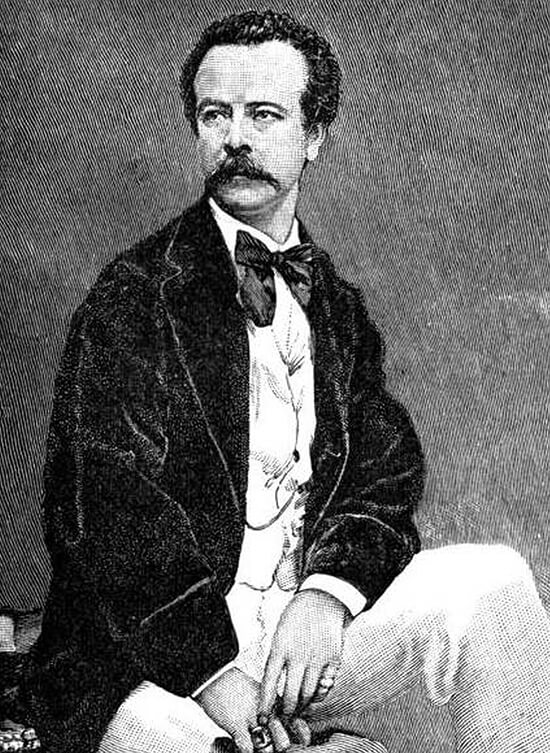

Worth: The Englishman who transformed French haute couture

High fashion has its roots in Paris and French culture. But do you know that it was actually an Englishman who transformed Parisian couture by establishing practices that laid the foundations for modern fashion as we know it today?

“Worth, Inventing Haute Couture,” the exhibition co-curated by the Petit Palais and the Palais Galliera in Paris, shows just how revolutionary Charles Frederick Worth was in the second half of the 19th to the 20th century by protecting couture designs, being the first to create seasonal collections, using live models to present his pieces and shifting the power from client to designer—earning the title “The Father of Haute Couture” from many fashion historians.

With no less than Empress Eugénie as his top client, bringing in European royalty and the aristocracy along with her, Worth created the most exquisite gowns of the period seen at the most lavish balls from Paris and London to New York and Boston. At the House of Worth, “one can experience so viscerally the heady sensation of luxury, of sumptuous elegance, of the superfluous, at once fragile and triumphant,” a writer observed in Le Figaro in 1905.

This was a world away from the beginnings of Charles Frederick Worth, born in 1825 in the Lincolnshire market town of Bourne to William and Ann Worth. Charles’ father, described as “dissolute” for mismanaging finances, left the family in poverty in 1836. The young Worth had to work at a printer at age 11, later moving to a London textile store then finally to Paris in 1836, where he became a sales assistant in the prestigious firm of Gagelin-Opigez & Cie where he met Marie Vernet, who became his wife in 1851.

Gagelin, which sold silks and cashmere shawls to court dressmakers, exposed him to the world of fashion and luxury. He designed dresses to complement the shawls and eventually headed a dress department. Despite his success in bringing in more clients and his help in building the company’s image through prize-winning designs at international expositions, he was refused a share in Gagelin’s business, prompting him to open his own shop at Rue de la Paix in 1858.

A ball gown that he designed for Princess Pauline von Metternich in 1860 proved pivotal when it was admired by Empress Eugénie, who demanded an appointment. “And so, Worth was made and I was lost,” wrote the princess in her memoirs, lamenting how “from that moment there were no more dresses at 300 francs each.”

The business of couture was also never the same again. Whereas before, clothesmakers would visit their clients who had fabrics and designs they wanted executed, this time, clients would go to Worth who offered an exciting range of fabrics and designs. Using his wife as his first model, he kickstarted salon shows to sell a collection.

He always guided clients on what suited them, establishing the role of the designer as style dictator. His son, Jean-Philippe, recalled how “his practiced eye discerned the color and style that would enhance a woman’s charm, and with complete serenity she might leave the matter to him and give her mind to the contemplation of home affairs, her children and philanthropies.”

As his fame grew through fashion magazines, more collections were made, and so were the knock-offs, leading him to introduce another innovation—sewing in labels with his signature and the particular season of the dress. This was particularly crucial when US President McKinley raised duties in 1890, making the export of fashion too costly and making plagiarizing rampant.

In 1868, Worth actually founded the Chambre Syndicale dela Haute Couture (which later became the Fédération de la Haute Couture and remains France’s governing fashion body) to protect the designs of couture houses from copying and to promote Paris as the fashion capital of the world.

Americans were some of his favorite clients because his French language skills never reached fluency, and “they have faith, figures and francs—faith to believe in me, figures that I can put into shape, francs to pay my bills.”

Not that his business in the continent was wanting. The empress alone was insatiable, once ordering 250 gowns just for the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Other royals like Empress Elizabeth of Austria aka Sisi, and even those from as far as India, Egypt, Japan, and Hawaii kept the house busy.

The number of pieces ordered by even one client could be overwhelming, considering the custom of the time to have so many outfit changes in a day, depending on the activity and occasion, as demonstrated in the exhibit’s panoramic staging of a wardrobe set from morning till night.

Demand was so great that the house charged exorbitant prices, and the higher the prices, the greater the demand grew. From starting with 50, the staff swelled to over 1,200 working on pieces that required painstaking attention to detail, finesse, and craftsmanship: A bodice can take up to 17 pieces of material to ensure a good fit. Different workshops were created, each one to specialize in a particular part of the garment and a particular finish.

Although most of Worth’s order books have disappeared, records exist from the early days of Louis Vuitton who made the trunks to transport his couture; and Cartier, who created jewelry to match—both featured in the exhibit which showcases some of the most sumptuous dresses like that of Countess Élizabeth Greffulhe, the inspiration for Proust’s Duchess of Guermantes of À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. Worth himself is immortalized in Émile Zola’s La Curée as the fictional Worm, “the genius tailor, before whom the Second Empire’s rulers took to their knees.”

With this tribute exhibit consisting of over 400 works that include painstakingly restored clothing (a very long and costly process sponsored by Chanel), accessories, art objects, paintings, illustrations, photos, and rare items on loan from various museums that include the Victoria & Albert, Palazzo Pitti, Uffizi, Metropolitan Museum, as well as private collections, one can see the breadth and depth of Worth’s contribution to fashion and that his legacy will certainly live on.