Rick Owens: The dark prince of fashion

PARIS—If Karl Lagerfeld was the Kaiser or emperor, Rick Owens is a prince, but not the wholesome Disney variety, as his retrospective, “Temple of Love,” at the Palais Galliera unequivocally attests, with even a gabinetto segreto that’s rated “R.” Owens has regularly shocked audiences, both with his catwalk shows, his clothes, and all other media that he has dabbled in.

Entering the dimly lit main hall of the exhibit, you may think that he has been reformed. The installations are like altars with some elongated mannequins dressed like monks in robes, positioned like a choir by the tabernacle, with side chapels featuring gowns in muted shades, from old white to dust and dark shadow.

There’s the soundtrack of what seems like a priest speaking in Latin at High Mass, which turns out to be Owens reciting lines from Joris-Karl Huysmans’ À rebours, which he discovered in his father’s library during his youth in Porterville, a small town in California where he had his beginnings as a “redneck.” He identified with the novel’s hero—the eccentric, ailing aesthete Jean des Esseintes, the last scion of an aristocratic family who loathes 19th-century bourgeois society, from which he retreats to create an ideal artistic world.

Owens’ hybridity, with a Mexican mother and an Anglo-American father, coupled with a Catholic education and a strict upbringing filled with classical music and philosophical and literary lectures, found him in the same trajectory as Jean. He discovered biblical accounts and rare works ranging from 19th-century French literature to early major Hollywood films that captured his imagination.

Films of Cecil B. DeMille made him lean into the elongated silhouette of 1930s bias-cut sheath dresses, but he went beyond mere historical pastiche by perverting them through “decayed glamour,” simulating the traces of time through different treatments—“degradations” that evoke his own vices—part of the autobiography that characterizes his oeuvre.

Another influence is Gustave Moreau, whose painting “Salome Dancing Before Herod” (1876) is described in Huysmans’ novel. Studies of the work are on display with gowns from 1997 and 2001, showing how their mystical aura and pictorial sophistication have a profound effect on the designer’s aesthetic.

Art school in the ’80s introduced Owens to Joseph Beuys’ art, “full of unique romance, drama, humanity, empathy, myth and mystery.” Owens’ use of felt is credited to the artist, a WWII aviator who crashed in Crimea, where he was saved by Tatars who wrapped him in felt blankets. The fabric became a symbol of protection and isolation, which the designer employs as a protective shell. When he moved to LA, he sourced felt from army surplus blankets that had the soldiers’ initials—virtual war relics that reminded him of the fragility of peace and protection, constant themes in his collections.

His move to LA jump-started his fashion career, meeting his future wife and business partner, Michèle Lamy, who offered him a job as a pattern maker at her design studio. By the early ’90s, he began to sell his first creations under his own name as Lamy abandoned her brand and became a restaurateur.

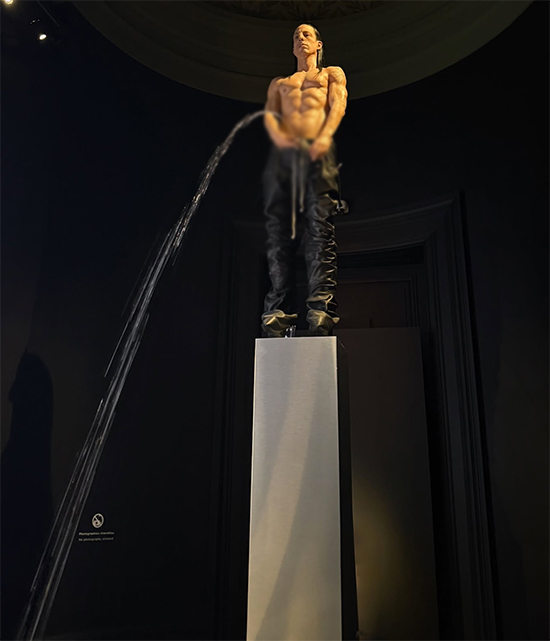

It was also in LA where Owens discovered the underground and sex club scene, a period that informs his work and is immortalized in “The Joy of Decadence” in the secret room of the exhibit. His naked wax figure—his version of Brussels’ “Manneken Pis”—greets you, acting as a centerpiece fountain with the water stream forming an arch through which videos of BDSM and other erotic practices either engage you or scare you away.

The designer maintains that in a world that can be very judgmentally condemning and overly moralistic, he feels a responsibility to counterbalance it with a “cheerful depravity.” It’s an attempt to “defy the hypocrisy of society, where violence is omnipresent in the streets and on screens,” while supporting artists whose role is to challenge conventional thought. Although these images provoke misunderstanding and criticism, the designer says that “they are based on defending otherness with kindness and love.”

After recovering from the assault on the senses, we returned to the main hall of more subtle transgressions. There were actually gowns with pearls, but not of the grandma variety—they’re concealed under jersey, recalling what he read about the Yakuza and how they inserted pearls in their genitals. This collection was from the ’90s era when he was living under the threat of AIDS, and exploring body modification was a way for people to deal with fear and rage and reclaim ownership of their bodies.

Nearby are more classical pieces, draped à la Madame Grès, who is a great influence, or reminiscent of Belle Époque silhouettes like the gown in the poster by Toulouse-Lautrec for the play La Gitane.

The final hall, containing collections from 2003, when he and Lamy moved to permanently settle in Paris, faces the garden and the sun—quite unusual for an institution that preserves fragile clothes in dark archives. But then, the possible discoloration of the pieces is part of Owens’ creative process, which integrates these deteriorations as “a reminder of life’s trials and sorrows.”

Here, his aggressive and sumptuous creations, often compared to Brutalist architecture, began to be presented in increasingly spectacular fashion shows, including one with male models in outfits that displayed their private parts—a statement on toxic masculinity and the objectification of bodies.

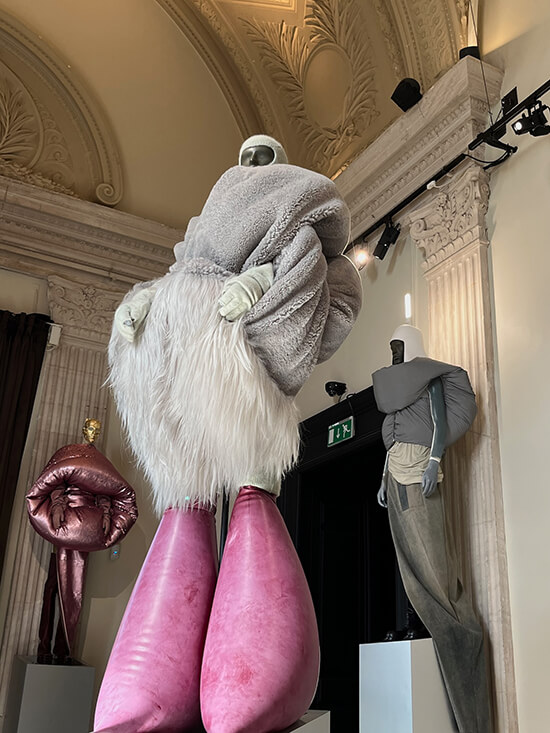

From 2013 onwards, his collections acquired a moral dimension, responding to intolerance in the West and inaction on climate change by increasing the proportions of his designs, likened to sculptures as emblems of protest. During the pandemic in 2020, he embarked on a meditation on history and time, calling for human humility in the face of our species’ insignificance.

From that period on, there were more intimate references and an unexpected tenderness—an ode to love and tolerance as the ultimate defiance. These musings presaged the title of the exhibit and sum up his work, dedicated to always finding the best alternatives to the standard cultural aesthetics that he felt were not inclusive enough. Always the outsider, he emulated his hero, Jean des Esseintes, who “soared upwards to dream, seeking refuge in illusions of extravagant fantasy, living alone, far from his century, among memories of more congenial times, of less base surroundings.”