Cartier: The jeweler of kings, the king of jewelers

LONDON — Even on a weekday, the Cartier exhibit at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London was heaving with jewel fiends swooning over more than 350 jaw-dropping pieces that include gobstopper-sized diamond rings, overwhelming swags of necklaces, and dazzling tiaras, secured from international museums, royal collections, and private collectors.

We, of course, were among the swooners, growing up with jewelry, Tanks and Santos watches at Rustan’s where Cartier had its beginnings and eventually expanded to stand-alone boutiques. Manila’s most elegant women would be seen wearing the most exquisite pieces from the house. If Cartier is one of the most recognizable names in jewelry and a world-renowned symbol of luxury, its success can be attributed to the three brothers—Louis, Pierre, and Jacques—who inherited the business from their grandfather, Louis-François Cartier, who founded the house in 1847. They expanded the Paris workshop into a global brand, with Louis as the creative visionary and designer, Pierre handling the business in New York, and Jacques managing the London branch while lending his expertise in gemstones.

You can’t imagine that the house had humble beginnings. “It was a small family firm, barely even a business, just a little workshop struggling to survive in difficult times,” says Francesca Cartier Brickell, Jacques’ great-granddaughter. “When Louis-François Cartier set up the business in 1847, he had a revolution to contend with in his first year of operation—no easy undertaking to sell diamonds when people are so hungry they’re forced to eat rats.” The only son, Alfred, kept the firm afloat by buying jewelry at knocked-down prices from desperate Parisians and selling them across the Channel to English aristocrats.

When the firm did get its bearings, it produced some of the most beautiful pieces from 1900 to the 1940s, displaying impeccable craftsmanship and technical ingenuity, establishing its reputation from that period on.

The exhibition explores this illustrious history, transporting you to Cartier’s world—from Indian Maharajahs to Belle Époque princesses and Russian duchesses—clients that the brothers encountered as they explored the globe for inspiration and rare gemstones.

The special relationship with English royalty is highlighted, as the exhibit opens with the magnificent tiara of the Dowager Duchess of Manchester, made in 1903 and displayed alone with its over 1,500 diamonds. This was just a teaser, saving a whole room full of tiaras for the grand finale, where owners are a veritable who’s who of the past century.

Some of the stunning ones include the 1937 Opal tiara of the Marchioness of Hartington, who wore it as a necklace at Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953; the Garland Style Scroll tiara from 1902, worn by Lady Churchill at the same coronation and by Rihanna for a W cover in 2016; and a 1934 Art Deco diamond and platinum halo tiara inspired by ancient Egypt, worn by Begum Aga Khan III. The Pineflower Tiara in emerald-cut aquamarines is another Art Deco piece, commissioned as an anniversary gift in 1938 by George VI for his wife, Queen Elizabeth.

Many of these royal jewels were loaned by King Charles III and his family, who have a long relationship with Cartier and were instrumental in boosting the house’s reputation from the time King Edward VII commissioned tiaras for his 1902 coronation and granted Cartier a Royal Warrant. Queen Elizabeth II’s famous Williamson brooch (1953), featuring the rare 23.6-carat pink diamond that she received as a wedding gift, was one of her favorites. Just as romantic but more controversial are the exquisite jewels of the Duchess of Windsor, commissioned by Edward VIII, who abdicated the crown to marry her despite the royal family’s disapproval of his marrying the twice-divorced American.

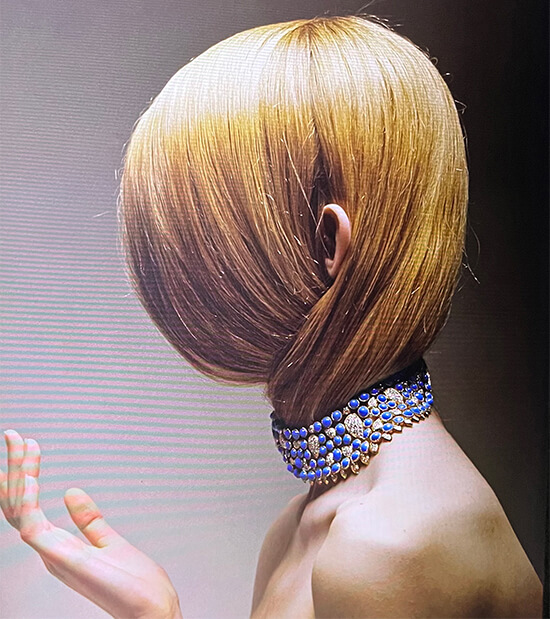

Other famous pieces are in a section devoted to materials: the necklace of American heiress Barbara Hutton, made from one of the finest collections of jade beads in existence; the Allnatt Brooch with a 101.29-carat vivid yellow diamond; and Mexican film star María Félix’s stunning snake necklace with lifelike movement.

From Hollywood, Grace Kelly’s engagement ring from Prince Rainier III has a place in film history as well as the gossip columns, since she wore it on set for her final film, High Society, in 1956, right before her marriage—one that may not have been the fairy tale it was imagined to be—a transactional solution to Monaco’s need for a royal heir and economic stability, requiring her to pay a $2 million dowry which her father, John B. Kelly, a self-made millionaire, initially refused to pay, saying, “My daughter doesn’t have to pay any man to marry her!” But he eventually agreed, draining his daughter’s inheritance significantly. Her married life was plagued by stories of the prince’s infidelities and her feeling of being in a “gilded cage.”

Elizabeth Taylor’s brief but passionate and flamboyant marriage to her third husband, Mike Todd, is commemorated in his gift of a necklace of diamonds and Burmese rubies that “lit up like the sun, made of red fire.” Barely 13 months after their wedding, Todd died in a plane crash, after which Taylor was embroiled in a scandal when she started an affair with her future fourth spouse, Eddie Fisher, Todd’s closest friend and husband of Taylor’s friend, Debbie Reynolds.

At the watch room, one can see the beginnings of the timepieces we wear today: The 1904 Santos, the first modern wristwatch designed to be worn by a man, heralded a modernity that would be the hallmark of all future Cartier models. The evolution of the Tank shows many iterations, including an important one owned by Jacqueline Kennedy, who was wearing it after her husband, President Kennedy, was assassinated, representing a private citizen’s life and becoming a symbol of her strength and resilience.

The multicultural room is one of the most interesting, reflecting how a fascination for far-flung places was at the core of many of Cartier’s important pieces: carved Chinoiserie objets d’art, tutti-frutti baubles inspired by the jewels of India, blue-glazed faience scarabs, and miniature sarcophagi from the “Egyptomania” period, which exploded after Howard Carter’s discovery of the Tutankhamun tomb. References from books are displayed, like drawings from Owen Jones, whose 1857 work The Grammar of Ornament depicts details of Cairo’s architectural decoration.

It’s amazing how all these were translated into mesmerizing jewelry and objects, bringing you to the heart of the house. These were, after all, the places and sources that sparked the imagination of the brothers and their craftspeople to create all the legendary jewels.

These inspirations drove them to dream, to experiment, to push creative and technical boundaries—creating pieces that surprise and astonish, a legacy that continues to this day.