The thin line between fandom and fantasy

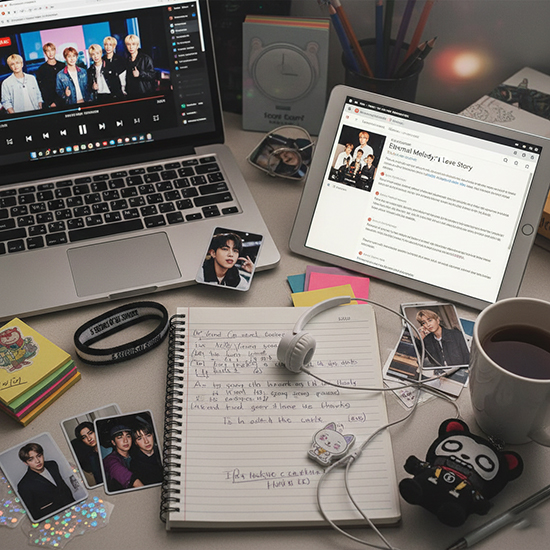

In the dim glow of a computer screen inside each of their bedrooms, thousands of fans anticipate a music video’s YouTube premiere, in accordance with a planned-ahead strategy to turn views into millions in less than a day. As if they are being paid for a 9-5 job, fans also flood social media with millions of posts to make hashtags trend.

It’s funny writing this now when I was on the frontlines of it before I even reached puberty. My history with fangirling started when I first heard What Makes You Beautiful by One Direction on our family’s car radio. A decade later, stan culture and I have made a whole lot of history.

Looking back, I realize how much fandom has shaped me into the person I am today. If it weren’t for publishing my Niall Horan fanfiction on Wattpad without any care for grammatical errors and plot holes, I wouldn’t have discovered my affinity for writing that later on sealed my college degree. Stan culture also taught me the power of human connections, even when they’re built solely on similar interests. For a massive population of pre-teens and teenagers who have all the time in their world, being part of stan culture is more than just a pastime. It is where heightened emotions and a sense of belonging collide. But at its core lies something both intimate and one-sided: parasocial relationships.

Sociologists Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl coined the term “parasocial relationship” in 1956. They observed that interactions between mass media users and media figures resemble typical social relationships: with the ‘50s seeing the golden age of television, people became enamored with the people they saw inside the box. As audiences saw the same celebrity or media figure onscreen, the repetitive exposure grew deeper, creating an illusion of closeness with people they had only seen in black and white.

Now, these bonds feel particularly potent in music fandoms, especially for male musicians and boy groups. From song lyrics that speak directly to the listener to candid livestreams and carefully curated content blurring the line between celebrity and friend, it’s easy to fall deep into this emotional rabbit hole. That is why, in 2015, when Zayn Malik left One Direction three days (!!!) after I attended their sold-out “On The Road Again” Manila Day 2 stop, I felt I knew what heartbreak was at the mere age of 11. When I jumped ship to K-pop, I felt close to Stray Kids because of their engagement with fans in frequent live streams and other online interactions.

A hard pill to swallow is that the groups we idolize are marketed to be what we see publicly. It is not always consistent with who they are behind the scenes.

It's difficult to distinguish whether the engagement is genuine or just a marketing tactic. But one thing is for sure. They are good at offering something real life doesn’t always give: safety, consistency, and the fantasy of perfect affection.

“The first fandom I’ve ever immersed myself in was 5 Seconds of Summer, which I discovered through One Direction,” Liam, my blockmate-turned-best friend from college, tells me. “I’d say I was the average updated fan. I’d listen to their music, catch up on news articles about them, follow fanpages, and read fanfiction.”

Rach, a friend from our BTS Army days, says the same thing. “I was a (5SOS) fan who was super updated with all their moves. I watched all their content and collected merch!” When I ask what type of fan she was, she says the magic word: “I was parasocial, to be honest.”

“It’s funny, but Wattpad made me parasocial towards 5SOS,” she continues, “and because of the meet-and-greets they were doing at concerts, 14-year-old me thought I had a chance with them back then.”

There is a reason why boy bands, or in 5SOS’s case, male musicians, are often the subject of parasocial relationships, especially with teenage girls. Entertainment companies would mold members into designated roles, essentially manufacturing these groups as products. The publicity machine is cranked, and a fanbase is quickly summoned. All of these images are carefully curated to benefit their management’s profit margins, not caring at all if this takes a toll on the members playing a fake version of themselves for a living. The result? A fanbase that feels like they personally know these boys, when in reality, they are buying into a character curated to earn their devotion.

In the book From Revolution to Revelation: Generation X, Popular Memory, and Cultural Studies, Tara Brabazon talks about how music groups would mark each member with attributes, specificity and personality. A prime example is the British girl group Spice Girls, where the members were marketed as individual personalities through distinctive nicknames and personas: Ginger Spice, Posh Spice, Baby Spice, Scary Spice, and Sporty Spice. These names helped the group foster relatability and achieve global fame by allowing fans to identify with a specific member and their respective sub-brand.

In the same book, Robbie Williams, a former member of the British boy band Take That, remembers how they were told what to say, how to behave, how to dress, and where they could and couldn’t go: “All the thinking was done for us. It was a prison, and I lived in that prison for six years!”

A hard pill to swallow for fans is that the groups they idolize are marketed to be what they see publicly; it is not always consistent with their personalities behind the scenes. Fanbases take a huge hit when idols do something out of what they are perceived to be. When I ask Liam if there was a moment when a group disappointed her, she answers: “When you hear a member of your most favorite band declaring they ‘don’t want to be a band for girls’ in a Rolling Stone article, you’re bound to feel discouraged from interacting with their music or anything related to them.”

I remember that 5SOS interview, published in 2015, like it was yesterday. 12-year-old me could not decipher what was happening, but I knew I was witnessing something drastic. Fresh from being the opening act for One Direction’s world tours, 5SOS’s budding fanbase consists mostly of teenage girls who saw the band as relatable, genuine and wholesome (despite their image being far from teeny-bopper boy groups). So when the members made casual comments about having groupies and perpetuating harmful stereotypes towards female fans, it sparked outrage both in and out of the fandom. Some were calling them out, while others were making #WeAreProudOfYou5SOS trend to declare their loyalty to the recently controversial group. I don’t remember reading the nine-page article that time; it was only when I left stan Twitter that I saw how vulgar and revealing the article was, a far cry from the “perfect” image I had of the group during my pre-pubescent years.

Rach describes the article as a “turning point”: “I couldn’t really see myself still supporting them not only as artists but as human beings. It was one of the first times as a fan that I realized, at the end of the day, we still don’t know the people we are a fan of.”

My friend Kei, who was once a big K-pop stan, left her respective fandom because of issues of fatphobia in the boy group she supported. She says the same thing about her fangirl experience. “Although we can give idols the benefit of the doubt, at the end of the day, we do not really know them that much to the point of defending them because of their own mistakes. Some fans would try to make issues smaller than they seemed back then, so it created a toxic environment within the fandom.”

It is not new to hear or see the phrase “parasocial relationship” floating around X (let’s be real, we still call it Twitter). It gets thrown around in online arguments to tell co-fans to disconnect from the internet (and touch some grass!). During fanwars—which often stem from petty causes like album sales and music show wins—some fans call others out to take a step back and realize that everyone is just a fan at the end of the day. These “wise” words get retweets and agreeing replies, but of course, they soon get forgotten. Social media is an echo chamber thriving on herd mentality. So it is a rare occurrence for someone to own up to their mistakes, as users tend to conform to the behavior and beliefs of the rest of the group. The cycle of fanwars and short-term clarity continues.

As much as fans have become aware of the bit of truth that has surfaced, they cannot deny that good things sprang out of being part of stan culture. Through 5SOS, Liam discovered her love for the rock genre and swarmed her way into rock and punk bands such as Green Day, Nirvana, and more. Rach tells me it was the people she got to be friends with, even after she left the fandom. For Kei, it was learning about different cultures, as she met people online who live outside the Philippines because of their shared interests.

Liam adds that celebrities are human beings as well, like us mere fans. “Some people we idolize are bound to be horrible people. We should learn to de-pedestalize these people, especially if their values and opinions on topics that matter don’t align with yours.”

It’s true that our idols can give us comfort and inspiration; in return, we have given them everything, even without them lifting a finger. These celebrities can thank their loyal fans for their support, but this can never replace the reality that they do not know us at a deeper level, and vice versa. It’s through self-reflection that we see this phase of our lives for what it truly is: entertainment.