Why do people collect maps?

A map is an attractive thing. As visual objects, maps are complex works of art that combine skilled drawing ability and printing techniques on a variety of surfaces that is most often paper, but can include animal skins, wood, or any other hard or semi-hard surface. Depictions of sea creatures, ships, and people, combined with elaborate cartouches which state the relevant details of the map, including dates and cartographers’ names, are all fascinating decorative touches that contribute to the beauty of a map.

An exhibition of maps, “Classics of Philippine Cartography from the 16th to the 20th Centuries,” has quietly opened at the National Museum of the Philippines-Cebu, with the aim of bringing to the Central Visayas audience a view of Philippine maps through the ages.

What is HAT IS cartography?

The art and science of map-making is known as cartography. There are many types of maps, and the most familiar, arguably, are topographical maps that outline geographical features and other information the map-maker, or cartographer, may want to convey, such as significant locations, place names, or natural resources. Information from seafarers, captains and expedition leaders was obtained by the cartographer who was responsible for the process of drawing, engraving, printing, and publishing the maps.

Maps as valuable political and navigational tools; Featuring Murillo Velardo map

As valuable navigational tools during the Age of Exploration, maps were closely guarded and prized for their information and accuracy, and used to further the political and economic ambitions of powerful nations.

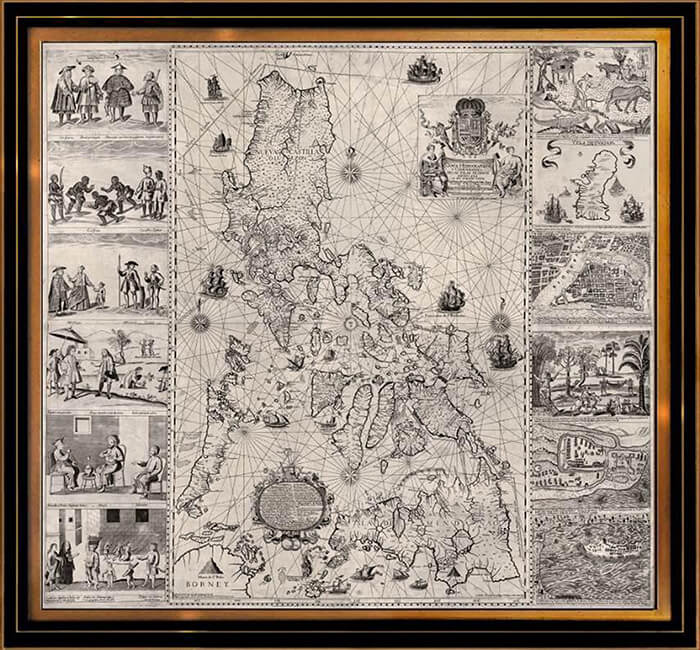

The 18th century map of the Philippines, created by the Jesuit Pedro Murillo Velarde SJ and engraved by the Filipino artist, Nicolas de la Cruz Bagay, was the first map to depict the Philippines accurately, and is also one of the most visually appealing, being framed on either side by 12 decorative plates depicting the inhabitants, native plants and animals, of “Yslas Filipinas,” as well as city plans of Zamboanga, Cavite, and Manila.

Historical aspects of maps; some revealing, others misleading

One interesting historical footnote of Philippine maps comes about through the later editions of Murillo Velarde maps. The earliest editions of the map indicate the maker, Murillo Velarde, as being a member of the Society of Jesus in the Philippines. A later edition, produced approximately 40 years later, erases this information, replacing it with decorative flourishes as by then, the Jesuits had been expelled from Asia.

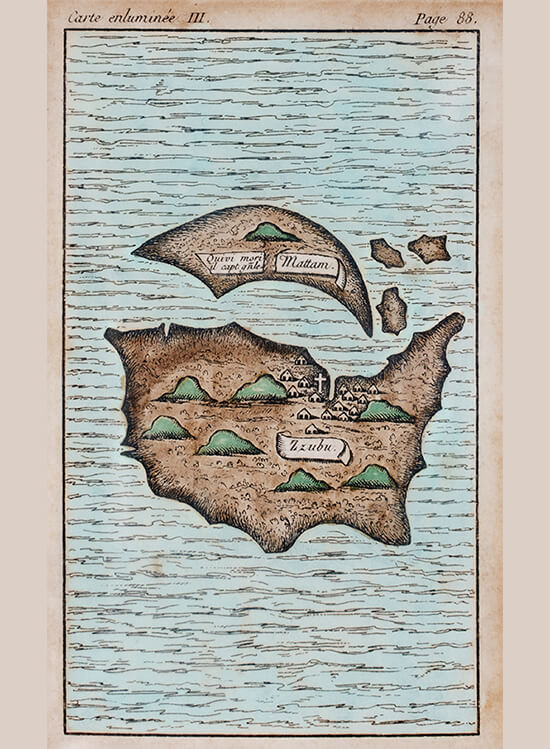

Maps could be misleading when they were inadvertently inaccurate, with the added injurious factor of multiple copies of erroneous maps produced through increasingly modern printing techniques. A well-known inaccuracy in maps of the Philippines was the frequent depiction of a non-existent small island or group of islands to the east or south of Mindanao. Often labelled as “Isle St John,” (or St Jean, or S. Giovanni, etc., depending on the nationality of the map-maker), this error was constantly repeated from the 16th to the 19th centuries, and remains a fascinating historical and visual oddity.

The attractions of maps, as expressed by collectors

In the Cebu exhibition, the wide-ranging selection of maps, some of which are quite rare, is drawn from the collections of members of the Philippine Map Collectors Society, or PHIMCOS, as it is popularly referred to. Far from being a dull group of collectors, I can attest, as a member, that PHIMCOS is a dynamic organization that functions much like a historical society of sorts. It organizes map exhibitions and holds lively quarterly lecture-meetings with talks on a variety of topics related to maps and prints. It has also conducted map-focused study tours, both locally and abroad.

I asked individual members of PHIMCOS as to why maps interest them, and their answers reflect the variety of uses and attractions of maps.

Andoni Aboitiz, chairman of the board of trustees of the National Museum of the Philippines, co-curator of the exhibition, trustee of PHIMCOS: “I am thoroughly fascinated by the confluence of art and history when I study maps.”

Marga Binamira, education consultant, co-curator of the exhibition, trustee of PHIMCOS: “Aside from history, geography and culture, maps tell the stories of what was important at a particular point in time: geopolitical power, economic trade, and societal beliefs. They also happen to be pretty to look at.”

Peter Geldart, retired financial executive, author of the exhibition catalogue, trustee of PHIMCOS: “I love maps because of the interplay between exploration, geography and history across the centuries. The variety is endless: manuscript and printed maps, atlas maps, maps in books, sea charts, town plans, thematic maps, etc.”

Jaime Gonzalez, chairman of Arthaland, president of PHIMCOS: “Old maps, particularly rare ones, are of great interest since it provides me a historical view of the world. It is a way to understand one’s culture and roots in a broader perspective, and it allows me to better appreciate our life today. It also illustrates how closely we are interconnected with the rest of the world.”

Rolf Lietz, proprietor of Gallery of Prints, founding member of PHIMCOS: “An antique map in a unique way compresses artistic beauty, historical significance, a sense of exploration and discovery, connection with a particular place, and adds monetary value due to collectability and rarity. The art alone of printed map creation, combining the efforts of a painter/sketch-maker, a cartographer, an engraver, a papermaker, a printer, a colourist and a historian/specialist, is absolutely fascinating and exciting—it is utterly unique!”

Raphael “Popo” Lotilla, economist, DENR Secretary, PHIMCOS member: “As mental constructs, maps mirror our image of the world. They give us a view of facets of human history as it unfolds.”

Albert Montilla, board member of Ortigas Foundation, founding member of PHIMCOS, also the oldest member at 90 years old: “My interest in maps started when I was still at the Ateneo Grade School in Padre Faura when I first encountered the subject of Geography. Since then and till now, said interest has not waned, especially maps on the Philippines and South East Asia.”

The exhibition “Classics of Philippine Cartography from the 16th to the 20th Centuries” is currently open until Jan. 31, 2026 at The National Museum of the Philippines-Cebu.

***

More information on The Philippine Map Collectors Society can be found at www.phimcos.org. With thanks to Marga Binamira and Peter Geldart of PHIMCOS and the National Museum of the Philippines, for the images used in this article.