How the German gaze made Rizal look twice

Without the German working women of the Lette Verein printing house would the world have had the Noli Me Tangere?

But it was more than German hands that sped our way to the Philippine Revolution; it was also the German eye.

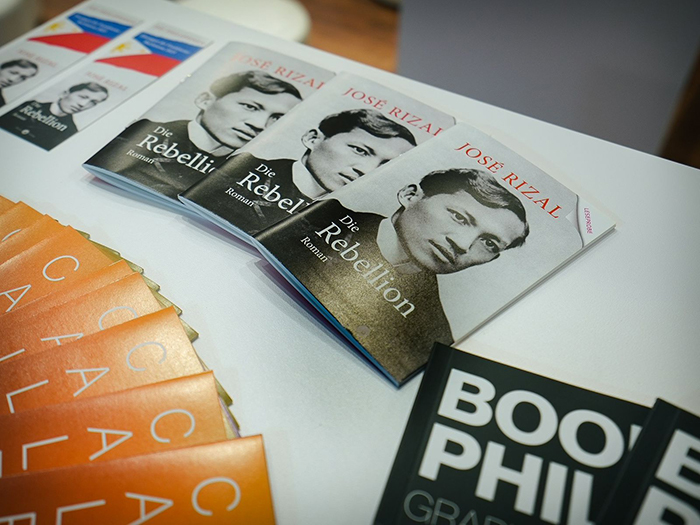

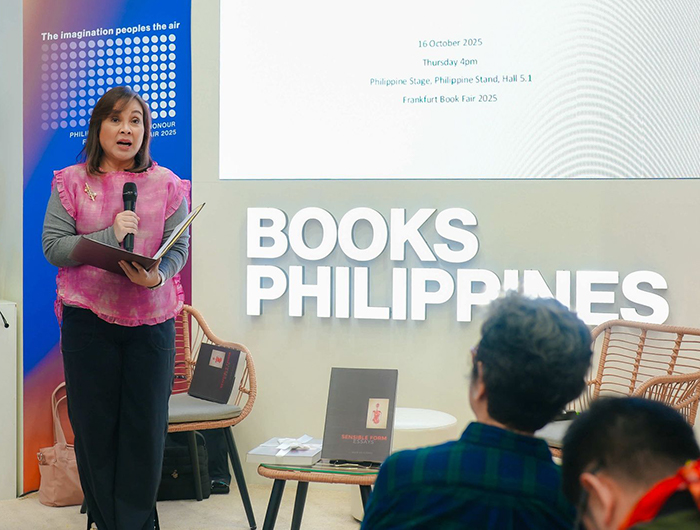

The Frankfurt Book Fair 2025 was a homecoming not only for Jose Rizal—who provided the majestic theme of the Philippines’ appointment as the Guest of Honour—but for the redeeming importance of the German gaze on our country and culture.

Rizal arrived in Frankfurt in August 1886; and on the very brink of his arrival 140 years ago, more than 500 Filipino authors and publishers, filmmakers and artists descended on the city that our national hero described as both “beautiful and elegant.”

Frankfurt in August is fairly warm and one can imagine Rizal venturing out on his walkabouts to see the Opera House or the Staedel Museum or the Goethe Plaza without even his overcoat (made notorious by Ambeth Ocampo, as a symbol of a distant Western colonialism).

How strange, nevertheless, Rizal must have seemed to the Germans. Slight of build (his suits displayed at the Rizal Shrine in Fort Santiago tell the tale of someone about 5’3”), his color was olive, and from his own letters, he was often mistaken for a Chinese person.

To add to the confusion of the Germans he would meet, Rizal had developed the disconcerting ability to speak and write in excellent German— and even to quote whole pages of Schiller, the country’s most beloved poet and playwright. (Rizal was a sponge who soaked up greedily his daily lessons with his benefactor, Pastor Karl Ullmer, with whom he roomed in Wilhemsfeld, a farming community outside Heidelberg. Ullmer noted that Rizal had the uncanny ability to hear a poem just once and be able to recite it to the letter afterwards.)

The horde of Filipino delegates who arrived in Frankfurt for this 21st century Buchmesse were just as unusual enough to turn heads—the men decked out in gorgeously embroidered long coats and cravats, the women in silk waistcoats with stiff, tall sleeves. All of them spoke a snappy American English, loud and friendly as people in a Texan barbecue, and enveloped by music of all kinds that followed them around the city.

Filipino history repeats itself at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2025

The commanding general behind this invasion was none other than Senator Loren Legarda, who drew on all her powers to acquire the top spot for the Philippines as Guest of Honour at the Frankfurter Buchmesse, the world’s oldest and biggest book fair, certainly its most influential. Despite her persistence and determination, it still took the senator more than a decade to land this enviably plum position. It soon became apparent that it was worth every minute of her time.

Beyond the classical music, soaring melodies of the world-famous Madrigal Singers, T’Boli chants, and book launches and edifying talks every hour on the hour for all the five days of the Buchmesse, there were extraordinary windows to the Philippines through the diaries and travelogues of the German adventurers who arrived in the mid-19th century.

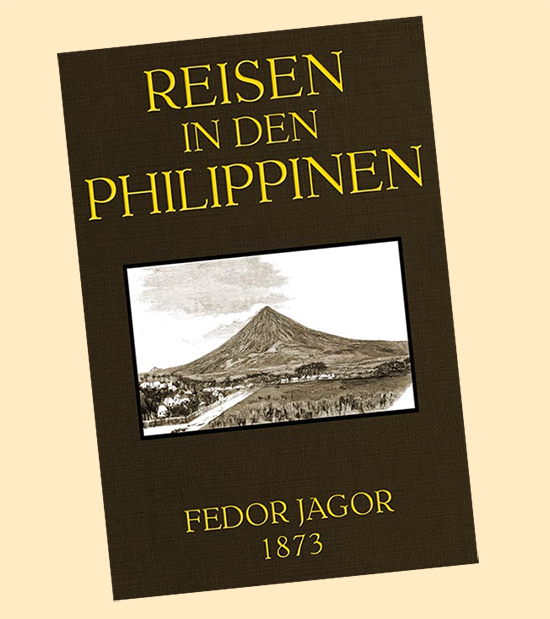

There’s more to this than meets the eye here. As early as the 1870s, German scientists beginning with the intrepid Fedor Jagor would begin to travel, explore and, more importantly, apply rigorous observation and analysis to the Philippines and Filipinos. In short order, they would establish themselves as the best-known resource on the country, outclassing even its own Spanish overlords. Jagor recorded the missteps of the Spanish regime (he even noted how Magellan sailed using the wrong measurements of time) and the neglect of a country and its people otherwise rich in forests and seas and mines—as well as art and industry.

In the quest to prove a pre-Spanish Filipino identity and culture—a necessary step in establishing a free nation—Rizal would thus find unexpected and unwitting allies among the German intelligentsia, who would objectively record what one historian would describe as “the pretend-progress” of the Spanish regime. Their candor was a sea-change from the anti-Filipino, pro-friar reports of the empire.

Rizal would thus fall headlong into intense relationships with Dr. Rudolph Virchow (the genius behind cellular medicine) who in turn introduced him to Jagor and Adolf Bastian and Wilhelm Lette (who would eventually print the Noli), all leading lights in the Berlin ethnographical community.

These connections were brought into sharp focus in Frankfurt.

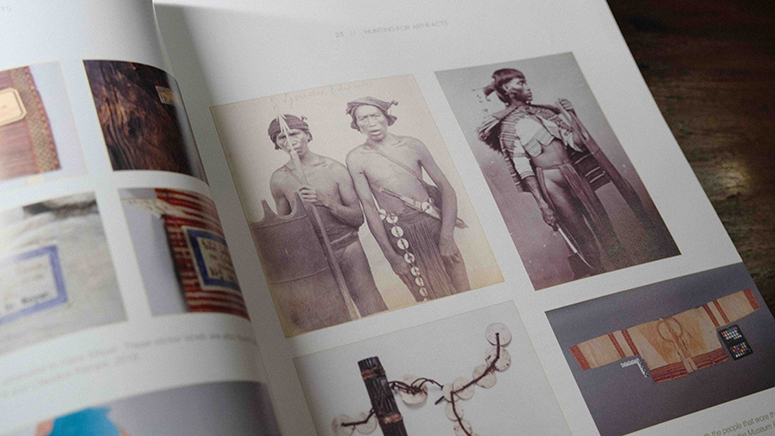

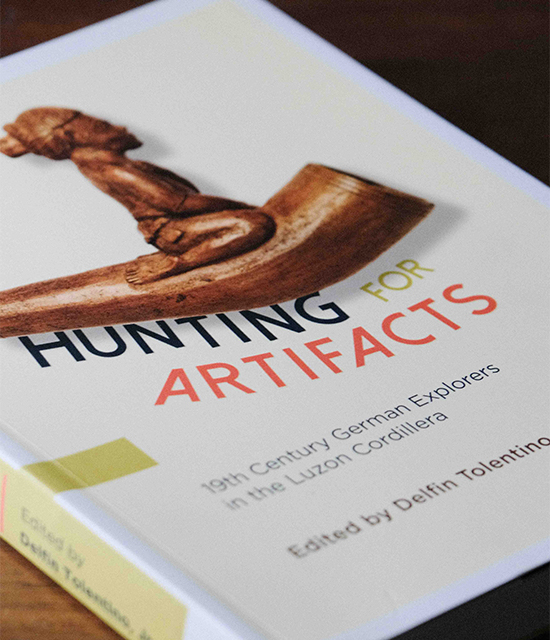

Among the important highlights were the launch of the scholarly tome Hunting for Artifacts: 19th Century German Explorers in the Luzon Cordillera edited by Delfin Tolentino, Jr. This book traced the numerous collections all over Imperial Germany, from Leipzig, Berlin, Dresden, Vienna, to Frankfurt itself, reflecting how widespread and important the study of the Philippines had become.

As a stunning prequel, there was a sound installation titled “Pagtatahip/ Winnowing /Windsichten”—an ambisonic /wave-field synthesis by meLe Yamomo at the Berliner Humboldt Forum Listening Space. One of the finds was the discovery of wax cylinders in Germany that astoundingly recorded Kalinga music recorded in the 1930s, played back on 300 speakers. The artist Yamomo combined it with ambient sounds including his father’s voice and crickets chirping in the rice fields of present-day Alcala, Pangasinan.

More plot twists followed at the Frankfurt State Library where Ambeth Ocampo and Budjette Tan tussled over “Rizal’s Overcoat”—which inspired the aswang-slayer Trese’s outfit in the Netflix series of the same name. Its co-creator Budjette Tan spoke about his childhood filled with witches, white ladies, tikbalang and nuno sa punso, not uncommon in the Philippines. He said that no such mythical creatures populated the German countryside and hence the Filipino multiverse had a special fascination for this European country. (At Frankfurt, the book made another milestone with a Brazilian edition for its authors Tan and Kajo Baldismo.)

Master-curator Patrick Flores put together an exhibition in the very heartland of Rizal’s Germany, titled “Pieces of Life: The Philippine Collection” at the Völkerkundemuseum Heidelberg that runs until March 28, 2026.

Closing the circle was the presentation by the National Museum of the Philippines of “Connecting and Collecting: The Launch of the Rizal Ethnographic Objects from the Berlin Ethnographical Museum.” It featured 21 keystones of Filipino culture, from Rizal’s own silver-embellished salacot, a fire-making piston, and various garments from fine piña to T’boli belts. It represents Rizal’s discourse with the German intellectual community and his emblematic messages of the Philippine pre-colonial identity.

Senator Legarda, who also chairs the Senate Committee on Culture and the Arts, emphasized that this Philippine-German connection is rooted in mutual curiosity and intellectual generosity, with its most resonant symbol found in the life and work of Dr. Jose Rizal.

“Rizal’s immersion in Germany and his correspondence with European scholars deepened our understanding of the world and our sense of national identity,” she said.

“Every artifact and story carries powerful claims to memory, belonging and identity—and allows us to question, reinterpret, and celebrate heritage on our own terms,” Legarda noted.

“As we embraced this prestigious role as Guest of Honour at the Frankfurter Buchmesse, let this renew our commitment to recognize that cultural preservation is not merely an act of commemoration, but a pledge to justice, solidarity and creative exchange. May it inspire ongoing conversations, responsible stewardship, and a future where history is remembered, revisited with openness, and continually transformed by the courage to seek, listen and care,” Legarda concluded.

Closing the circle was the presentation by the National Museum of the Philippines of “Connecting and Collecting: The Launch of the Rizal Ethnographic Objects from the Berlin Ethnographical Museum.” It featured 21 keystones of Filipino culture, from Rizal’s own silver-embellished salacot, a fire-making piston, and various garments from fine piña to T’boli belts. It represents Rizal’s discourse with the German intellectual community and his emblematic messages of the Philippine pre-colonial identity.