Not your show band, not your Superwoman

Every day, around 6,000 Filipinos fly out of the country to work abroad, enough to fill the SMX Convention Center to full capacity. A significant portion of them are musicians and entertainers. With more than half of them earning less than P20,000 a month locally (according to a 2024 study by the Musika Pilipinas Project), and with the lack of stability and social security for creatives in general, Overseas Filipino musicians are eager to take their chance for a better life overseas. Building on the reputation of Filipinos as great singers and versatile musicians, one is sure to find a Filipino musician in almost every corner of the world.

This is the context from which the Filipino Superwoman Band—an ensemble composed of Eisa Jocson, Bunny Cadag, Cathrine Go, Teresa Barrozo and Franchesca Casauay—draws its energy. Formed in 2019, the “pop-up girl band” has returned to the Philippines for a performance in Quezon City. As someone who worked as a freelance musician for a good part of my early 20s, I was curious to experience this one-of-a-kind show band live.

I recall when I auditioned as a drummer for a country band in La Trinidad, Benguet, I was instructed to never stop and to “keep the beat” for four hours, with only a few breaks in between. Medleys provide uninterrupted live music for dancing, but they demand a high level of skill and endurance from musicians.

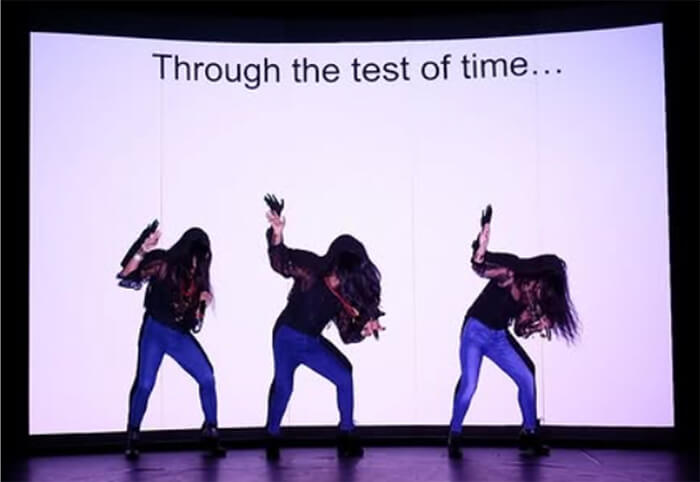

Fittingly, the band’s performance starts with a medley of popular “diva” hits, remixed and chopped up to the point of stuttering. We are finally introduced to Jocson, Cadag and Casuay, singing and gesturing small phrases from the mix of Beyoncé and Celine Dion snippets. Is the stuttering a response to the endless medley form? Through the band’s deconstructed execution, the audience is given the opportunity to inspect the choreographic conventions usually employed by Filipino biriteras. The section eventually ended with the three women shimmying to stage right to get water, apparently ending the set. But no: they returned to the stage, water bottles in hand, and drank their water with flair, in perfect unison. The audience bursts into laughter. Clearly, there is no need to take the show too seriously.

This Superwoman Band was truly supernatural, because on top of the singing, they had to dance, interact with the audience and crack jokes. And make no mistake, these are all part of the performance. After all, Filipino entertainers also take on the burden of affective labor on top of the actual singing. In fact, these strategies have become part of a typical Filipino live performance. From asking the audience “Sinong brokenhearted dito?” to having a full-on catharsis onstage, the Filipino entertainer is not simply belting out notes, but also taking on the unexpressed “affect” of the audience, singing as their mouthpiece and moving as their proxy martyr. The Filipino Superwoman Band demonstrates this by parceling out the movements and gestures of the singing body, served piece by piece to the crowd. Barrozo’s live scoring elevates the theatrics using sound effects that lend the performance a lively noontime show atmosphere.

But while the spectators are made aware that the band is “serving” them/performing to keep them entertained, the band also occasionally breaks the barrier between themselves and audience. These conversational improvs between the band and its audience, a common feature in music bars and comedy clubs, allow the band to turn the tables and render the audience more vulnerable. In between the performances, the band surveys the room, asking viewers random yet intimate questions, making us sing, stand up, wave our hands in the air. The audience, previously comfortable in their role as recipients of spectacle, is now periodically put on the spot, never settling into privileged non-attachment. But the openness also allows a deeper connection among everyone in the room.

The main course, however, is the band’s karaoke rendition of the song Superwoman by Karyn White. For this iteration, the band weaves in Hindi Ako Si Darna, a Filipino adaptation by Jenine Desiderio. In every repetition, Casauay has erased different words from the lyrics projected on the wall, pulling the song into different directions.

There are three iterations—Libertine, Lover and Laborer—each representing a face of the Filipino entertainer. Libertine illustrates the woman not as a giver but as an enjoyer of pleasure. Lover, meanwhile, portrays the woman not as the object of love, but as the active loving agent. Finally, the Laborer highlights the entertainer’s struggle as an artist and care worker.

The dismemberment of the text eventually gives way to the melody dissolving into the Pasyon. The karaoke disappears, and the three women now face the audience in unison chanting, the familiar Pasyon tune making the audience laugh, recognizing the melody. In a Q&A after the performance, Jocson mentions that Filipino audiences are amused by this part of the performance, while performing it abroad, audiences unfamiliar with the melody perceive the section seriously. The poet Jaya Jacobo, responding to the piece, said that she loved how the piece walks the line “between sincere and mocking.”

And this is ultimately what I love about watching the Filipino Superwoman Band, this refusal of categories in the face of radical joy. Was the band mocking when they mentioned the names of the institutions and galleries that funded them in the exaggerated tone of over-enthusiastic emcees? Was the band sincere when they sang Superwoman in the tune of Pasyon? It doesn’t matter, as long as the band has fun onstage, and the audience is laughing and crying with them.

I find art that represents overseas musicians and entertainers as capable of experiencing both joy and rage rather rare. As the government continues to peddle overseas entertainers as a cheap export, it is refreshing to see works that break the condescending narrative of migrant workers as superheroes, and instead portrays them as full-fledged individuals with deep passions and struggles. By dissolving boundaries between labor and play, between performance and life, the Filipino Superwoman Band illuminates the full spectrum of what it means to live and make a living onstage.