The shifting tones of realism

One can say that realism has been a sustained performance in Philippine art—an ever-evolving gesture that captures the mood and temperature of a moment so acutely that it becomes, almost by default, the emblem of its era. If one seeks proof, one only need look at the sweep of works gathered for Leon Gallery’s recent year-end auction, “The Kingly Treasures,” that hit the gavel last Saturday, Dec. 6, at G/F Eurovilla 1 on Rufino and Legazpi Streets in Makati. Across 160 lots, we witnessed how realism—whether social, psychological, or fabulist—continues to shape the ways we see ourselves and the stories we tell.

The lineage, of course, is long and storied, marked at this auction by the presence of Juan Luna, whose shadow still hangs over Philippine painting like a stern but brilliant ancestor. Yet what feels invigorating in this selection is how midcareer artists—those firmly rooted yet still inventing their own vocabularies—are steering realism into new territories.

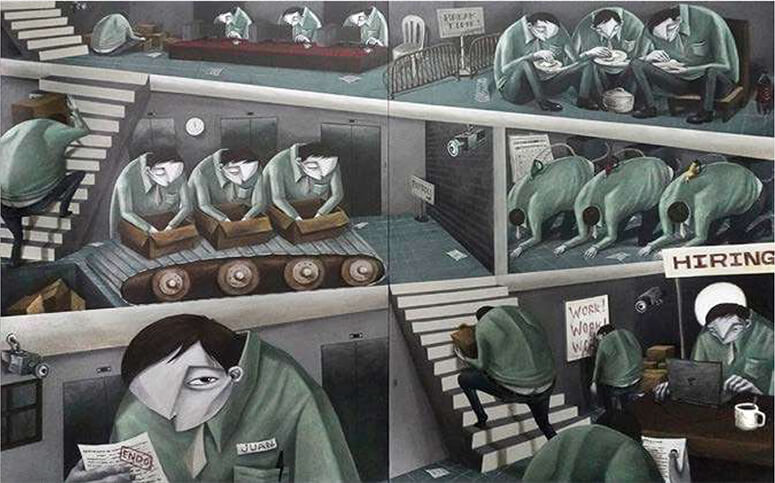

Cedrick Dela Paz’s “Middle Class” is realism rendered as indictment, a panorama of the grinding machinery of labor. His figures, hunched and uniformed, move through the tiers of a cramped building like parts in an assembly line. They pack boxes with robotic resignation; they eat in synchronized fatigue; they cycle in and out of “ENDO”—the dreaded end-of-contract notice—only to queue for rehiring. The entire composition resembles an anthill of ceaseless motion, but one drained of the dignity of purpose. It is a portrait not of individuals but of a class made tired, made replaceable, made to repeat its own undoing.

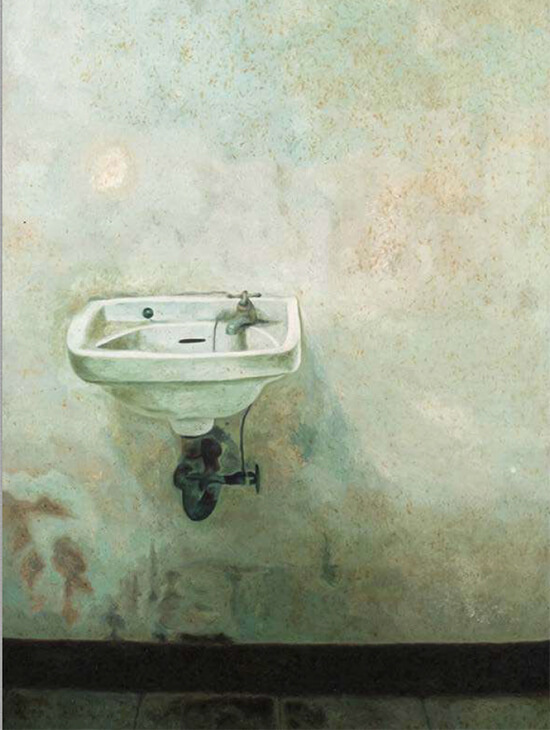

In another register is Nona Garcia, whose untitled painting (72 x 48 inches) dwells in the stripped-down vocabulary of stillness. On a vast, mottled wall, a lone sink clings like a relic exposed by time. The surface around it blooms with stains, discolorations, quiet wounds—marks left by hands long gone. Garcia’s realism is ascetic yet charged; the sink is rendered with a clarity that feels almost ceremonial. It stands as a vessel of repetitive, unseen gestures: washing, rinsing, erasure, return. In its spareness, the work becomes less an object portrait than a meditation on the anonymous caretakers of our spaces. It is realism turned inward, toward silence, toward the ache of the unremarked.

Then there is Rodel Tapaya, whose mythico-realist world ruptures the familiar. His painting unfurls like a fevered tapestry: a colossal galleon suspended over a verdant, surreal landscape; blue roses blooming at the edges like emissaries from another realm; a masked figure peering through a telescope beside a miniature pagoda; cascades of water slicing the terrain into fragments. Tapaya’s tableaux are always dense with symbols, but here the voyage dominates—the looming ship carrying with it echoes of colonial incursion, maritime crossings, and histories of displacement. Yet the improbabilities within the scene—oversized flora, skewed scales, the blend of theatrical and everyday objects—suggest the porousness of memory itself.

Taken together, these works reveal how realism in the Philippines is less a single tradition than a shifting spectrum: from the sharp edges of social critique to the restrained pulse of introspection, all the way to the charged dreamscapes where history is rewritten in symbols. In the end, realism is only one chapter in the vast, unruly story of Philippine contemporary art. But its enduring power—its ability to register the tremors of society, to articulate interiority, to hold memory in paint—remains unmatched.