Beyond the P500 bill: Kiko Aquino Dee carves his own path vs. corruption

In the tumultuous political landscape of the Philippines, where historical memory often battles deliberate forgetting, a new generation of leadership is emerging—one that is rooted in legacy yet determined to carve its own path. Among them stands 33-year-old Francis Joseph “Kiko” Aquino Dee, a name that echoes through Philippine history yet speaks with a distinctly contemporary voice.

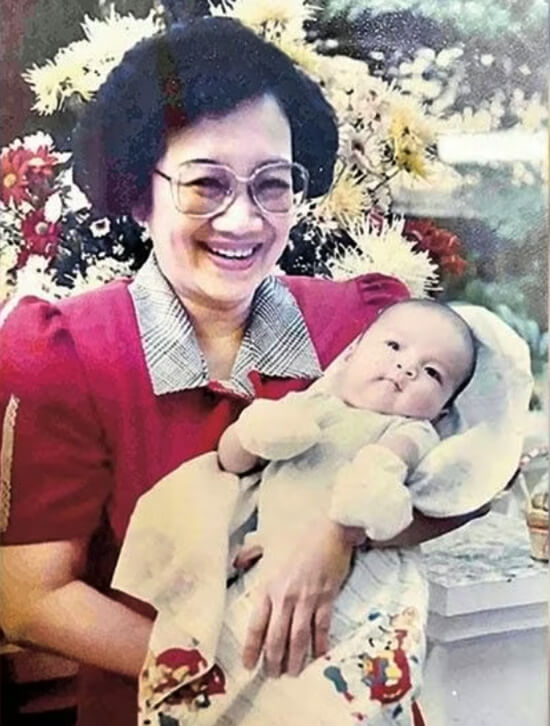

The spokesperson for today’s “Trillion Peso March” against corruption, this soft-spoken University of the Philippines political science senior lecturer embodies both the enduring power of moral conviction and the evolving nature of democratic engagement. A magna cum laude UP graduate and alumnus of the London School of Economics’ MSc program in Political Science and Political Economy, Kiko wields a potent combination of academic rigor and deep familial legacy—as the grandson of Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. and former President Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, and as the grandson of my late uncle, Christian philanthropist and Magsaysay awardee Ambassador Howard Q. Dee—to confront the enduring specter of systemic corruption.

The significance of the Sept. 21 date hangs heavy—it is the anniversary of former President Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s 1972 martial law declaration. This year, it becomes a catalyst for mobilization, with twin protests converging in Metro Manila: the student and activist-led “Baha sa Luneta” at 9 a.m. at Rizal Park in Manila and the church-led “Trillion Peso March” at 2 p.m. at the Edsa People Power Monument in Quezon City, where Kiko serves as spokesman. In this moment, he represents something profound—the unbroken chain of resistance that connects past, present, and future.

A conversation with Kiko Aquino Dee: legacy, activism and the fight ahead

Last month, at the Aug. 21 anniversary of his grandfather Ninoy’s 1983 assassination, I asked Kiko some questions. His replies revealed the thoughtful complexity that defines his approach to activism and the weight of the history he carries. The following is our conversation, verbatim.

THE PHILIPPINE STAR: You were born after your grandfather Ninoy Aquino was assassinated. Growing up, how did you first come to understand who he was—not just as a family figure, but as a national symbol?

KIKO AQUINO DEE: When I was in second Grade, a classmate called me up (via landline) to ask if it was true that the person on the P500 bill was my Lolo. That might’ve been my first memory that he was someone important. I think I only realized how important my Lola, and by proxy, my Lolo, were when I saw my Lola lead protests during the terms of Presidents Estrada and Arroyo.

Without ever meeting him personally, how do you feel about how Ninoy’s ideals and sacrifices have shaped the values passed down to you and your generation?

I definitely think we have a greater attachment to the country. Lolo was a patriot, in a way not a lot of people are now. He just had such naked love for the country and its people. I think we all struggle to follow his example, especially when things in the country turn for the worse, but I imagine I’d be a lot more apathetic if it weren’t for his example.

As someone active in causes today, how do you see your work as a continuation—or perhaps an evolution—of your grandfather’s fight for democracy and justice?

I suppose it’s like a rebooted film. Not as good as the original but maybe a bit more relatable to contemporary audiences.

Recently, you made headlines for being escorted out of the Senate gallery after flashing a thumbs-down sign. How do you connect that moment of protest to the kind of defiance your grandfather embodied in his time?

I’m not sure if Lolo would’ve done things the way I did. More likely, he’d be on the floor making arguments to sway his colleagues. He’d be closer to Tito Bam in that sense. But I like to think that I’m using a different set of tools to fight for the same thing: holding the highest officials of the country to account.

Do you feel a sense of pressure or responsibility to live up to Ninoy’s legacy, or do you see it more as an inspiration to carve your own path?

I think my particular role is to tell his story. The pressure is less to live up to it and more to avoid dishonoring it.

If Ninoy were alive today, what issues do you think would he be most passionate about—and how are you and your generation responding to those same challenges?

It’s interesting because Lolo Ninoy could be passionate about any issue when he needed to be. His second privilege speech, I think, was about anomalies in the PCSO, and he talked about it as passionately as he did the corruption and creeping authoritarianism of the pre-martial law Marcos administration. I think my generation and those younger than me don’t usually lack passion. The challenge is figuring out how to translate that into tangible change.

The March for a nation’s soul

Both the “Trillion Peso March” and “Baha sa Luneta” rallies are not isolated events. They are a visceral response to allegations of trillions of pesos lost to “ghost” flood control projects—a potent symbol of the systemic corruption and ineptitude in government that infuriate citizens across the political spectrum. Its timing on the martial law anniversary is a powerful act of reclamation, transforming a dark date into a day of citizen empowerment and peaceful assembly.

Kiko Aquino Dee is the ideal spokesman for this movement: a scholar-activist who leverages his intellectual background from the world’s leading institutions to understand the theory of change, the weight of history, and the urgent, practical need to hold power accountable. He is not simply resting on the legacy of his name; he is curating it, protecting it, and building upon it for a new generation.

As people march today, they march not just against corruption, but for the promise of a democracy that truly serves its people. And in Kiko, they find a voice that is both an echo from the past and a clear, compelling call for the future—a voice proving that the truest legacy is not the face one inherits on a banknote, but the character one builds through one’s own convictions.