[OPINION] A martial law baby remembers

"Tipar tayo," invited a friend.

That was a typical inverted Tagalog slang, which meant "Let's party." '70s lingo included erpats (father), dehins (hindi), and jeprox (project). Parties were "stay-in," meaning one had to spend the night up to early morning because of curfew restrictions.

The imposition of curfew was just one of the restrictions of martial law.

Curtailment of rights

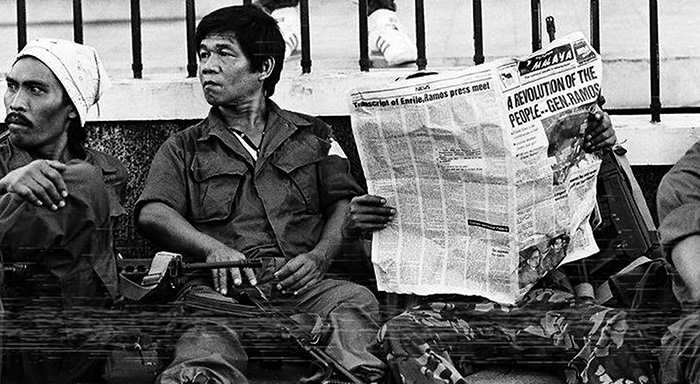

Aside from curfew, civil and political rights were suspended. Group assemblies were banned, media were heavily censored. Even on campuses, student councils and student publications were banned or heavily controlled.

The proclamation of martial law was dated Sept. 21, 1972. Although it was announced on Sept. 23, political enemies, journalists, activists, labor leaders, and ordinary citizens were already being arrested the day before its announcement

I was a sophomore in high school in 1972, undergoing a training program for Boy Scout officers. We were fast-tracking our training because the late President Marcos had just made scouting compulsory for all high school students. That mandatory rule made the Philippines the biggest scouting country in the world.

No jeeps, no TV

Our training was abruptly stopped when our scoutmaster woke us up and announced in the middle of the night of Sept. 23 that the president had declared martial law. We had no idea what it was all about. When we got out of school, the streets were eerily empty. When I finally got home, there was nothing on television until Francisco Tatad made an announcement. We were scared.

Marcos' pretext

The late dictator's pretext for declaring martial law was rising lawlessness arising from communist rebellion, sectarian violence between religious Muslim and Christian groups, and a Muslim secessionist movement. Previous to the declaration of martial law, there were massive protest rallies which peaked during the first quarter of 1970, now popularly called the First Quarter Storm. I was a grade schooler at San Beda Mendiola, and somehow, witnessing those frequent demonstrations in Mendiola had rubbed off on me.

More protests

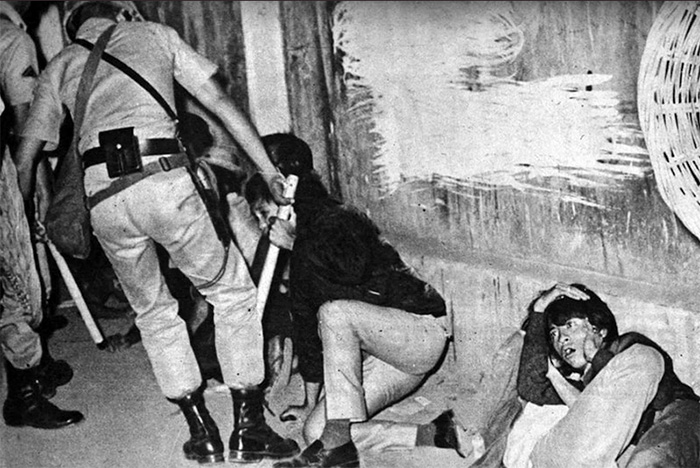

The following year, from Feb. 1 to 9, 1971, students and faculty members of the University of the Philippines barricaded their campus to protest the oil price increase and the use of military force on the campus. This became known as the Diliman Commune.

In August of the same year, Plaza Miranda was bombed during a political rally of the Liberal Party. Several people died and were injured.

Following the bombing, Marcos suspended the writ of habeas corpus, which allowed the Philippine Constabulary to arrest individuals without a warrant.

In 1973, the Philippine Constitution was convened to legitimize Marcos' authoritarian rule and consolidate his power.

I was in sixth grade in 1971, and I remember classes were suspended on our last grading period because of violent protests near Malacañang. My parents decided to transfer me to a safer school at the University of Santo Tomas, far from the violent streets of Mendiola. I skipped Grade 7, never graduated formally in grade school, and never saw my classmates again. I missed them dearly.

The dictatorship dubbed the martial law era as The New Society despite unlawful arrests, torture, and other forms of human rights violations. Some simply disappeared, becoming "desaparecidos." Corruption was also prevalent.

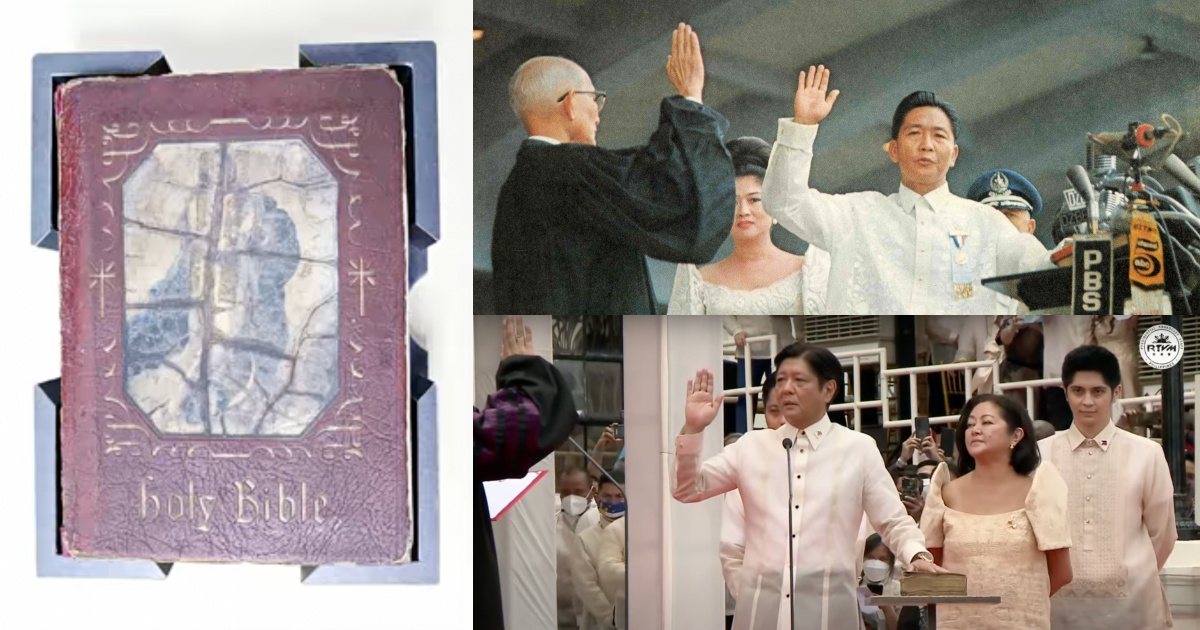

In 1977, curfew was lifted, but injustices continued. Finally, shortly before the visit of Pope John Paul II, martial law was lifted on Jan. 17, 1981. Marcos was still in power until his ouster in 1986 during the EDSA People Power Revolution.

For almost my entire student life, Marcos was the president. It seemed he would be president-for-life until EDSA came. I was never formally a member of any organization, but I kept myself informed on the real issues. I was called a sympathizer, some described me as "mulat" but through the years, I remained consistent, attending rallies, sometimes tear-gassed, from Mendiola to Liwasang Bonifacio to Ayala.

The EDSA Revolution brought hope and a change in leadership. Although the post-EDSA administrations were far from perfect, they offered a fresh start that did not last long.

Group amnesia

Now, the new generation seemed to have suffered amnesia by voting for the son of a dictator. Is that a result of lack of knowledge, misinformation, fake news, or simply apathy?

With the current exposès on flood control kickbacks, let us review the past, educate ourselves, and prepare for a radical change. The future is in our hands. As former Supreme Court Justice Claudio Teehankee has said, "The greatest threat to freedom is the shortness of memory."

Join an educational walking tour at the Freedom Memorial Museum Gallery, the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, and Quezon Memorial Circle on Sept. 21.

Thousands of protesters are expected to take part in two demonstrations in Rizal Park in Manila and the EDSA People Power Monument in Quezon City on the same day amid the flood control project scandal. Here are more details about the Sunday rallies regarding the program flow, the dos and don'ts, and other things that attendees must keep in mind.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the opinions of PhilSTAR L!fe, its parent company and affiliates, or its staff.