It’s time to talk about problematic sapphic representation on TV and film

Long before streaming confined us to our separate bedrooms, a shared family television kept the entire household entertained. It was my after-school routine to watch GMA’s Dramarama, a series of afternoon teleseryes often with melodramatic plots, before I caged myself with my Araling Panlipunan homework.

But like in a teleserye, my emerging interest in TV only served as an establishing plot device, a foreshadowing of what was to come. The more I grew up and steered my identity, the more I sought it in the media I consumed and hoped to see myself in the characters. But apart from The Rich Man’s Daughter, which had a time slot that met my 11-year-old self's bedtime, I certainly did not see an ounce of sapphic-ness in the dramas of my family TV set.

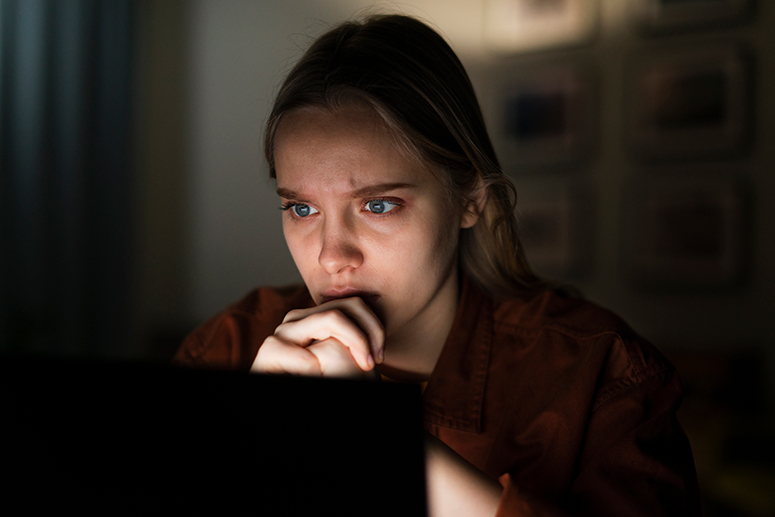

Come streaming, I desperately looked for anything to “justify” my identity. I rummaged through episodes, dissecting the 10-second screen time of the sapphic characters I watched it for, relentlessly pressing play, all for the sake of representation.

This exploration opened me up to a newfound sense of identity. I learned more about the sapphic—or women-loving women—experience through different lenses. However, a problematic pattern soon revealed itself. I repeatedly noticed harmful themes, such as unreasonable character deaths, queerbaiting, and hypersexualized scenes.

So I asked other young sapphic women: How can we redefine existing sapphic narratives?

‘Not just the sexual ones’

Elle, 27, recalled a conversation with a coworker about sapphic shows and films.

“The majority of what she mentioned, like Blue is the Warmest Color, directly caters to the male gaze. I told her that some of the shows and films she consumed are borderline porn. She said she doesn’t mind because it is still a story about WLW relationships.”

Objectification limits the emotional intimacy of sapphic relationships, reducing them to just sexual beings devoid of complexities.

Iah, 21, questioned if intimate scenes in most sapphic media exist just to provoke or satisfy the heterosexual audience.

“It is also important to have women behind the scenes. Also, we have to explore the important aspects (of the sapphic experience), not just the sexual ones.”

Loving women is one of the most beautiful things one could ever experience. Just as with any relationship, it includes aspects of cheesy romance and the awkward yet wholesome exchange of confessions of love that could be the centerfold of sapphic stories.

“If one of the main aims of the show is to tell the world our story, and if showrunners really love us, they wouldn’t do us such injustice through objectification blanketed under false representation,” added Uni, 21.

A love letter from the sapphic community

While there exists media that intentionally advocates for viewing WLW relationships through different lenses and stories, fair representation cannot be done overnight. As it remains a work in progress, we must listen actively to the sapphic community—the very audience of sapphic TV shows and films meant to represent.

“We have to have sapphic media that will serve as a positive step towards normalization, that will dismantle harmful portrayals rather than contributing to them,” Iah said. Sapphic stories, she added, can exist within coming-of-age stories, middle-aged stories, and stories about families.

However, Uni called for “more calm and chill storylines” set in normal, daily settings, rather than often intense and hypersexualized stories. She also hopes to see universal sapphic media; stories that can be understood by kids, families, and the elderly.

Elle, following Uni’s train of thought, also seeks a more friendly approach that will cater not only to specific demographics but the rest of the world, defying the blatant objection of WLW relationships and emphasizing the need for a pangmasa approach that everyone can naturally relate to, especially in the Philippines.

Some might say that TV shows and films are not to be overintellectualized but meant to be enjoyed, relished, and felt instead. However, the first condition of art is to represent human life, echoing Leo Tolstoy’s claim: “To correctly define art, it is necessary, first of all, to cease to consider it as a means of pleasure and to consider it as one of the conditions of human life.”

If such reflections of genuine life conditions are being misrepresented, or worse, absent, the crucial function of entertainment media as a pleasure will unsteadily flicker and may lead to a complete shutdown. When repeated misrepresentation through fetishization, tragic endings and objectification of sapphic stories continues to flourish, the screen that supposedly mirrors authentic stories of love and coming of age of women loving women becomes only a portal—devoid of any realities, palatable to and catering to the mainstream, not to the community, and definitely not to young sapphics desperate to tether onto something that represents them.