History in every dish

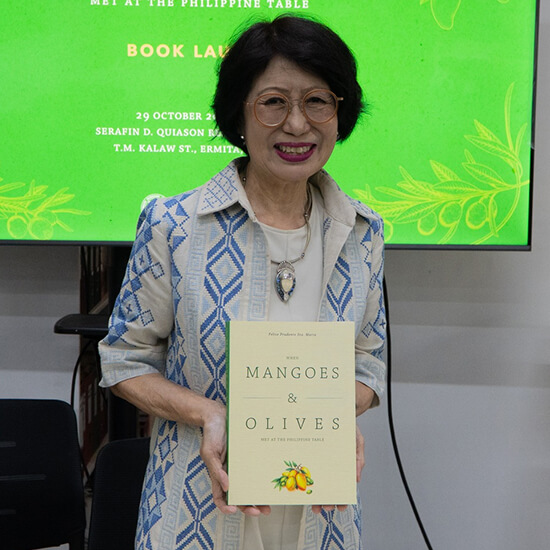

I’d say that the most essential food writer we have at present is undoubtedly Felice Prudente Sta. Maria. A few years ago she was awarded the Gawad Balagtas for lifetime achievement in the Essay in English by the Unyon ng mga Manunulat sa Pilipinas (UMPIL) or Writers Union of the Philippines.

Along the way, Felice joined a select group of food enthusiasts billed as FWAP or Food Writers Association of the Philippines—together with food columnist Micky Fenix, chef Myrna Segismundo, and coffee-table book publisher and designer Marily Orosa. They’ve been instrumental in perpetuating the memory of legendary food culture scholar Doreen Gamboa Fernandez, whose most memorable works (some co-authored with Ed Alegre) have been reprinted in various anthologies. FWAP has also ensured the annual tradition of organizing the DGF Food Writing Contest, since 2004.

But Felice also acts independently as an indefatigable heritage researcher whose literary produce goes beyond food writing. It is food history that she explores, and discusses with authority.

She has served in the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, as well as the UNESCO National Commission of the Philippines. In 2019, she initiated the Philippine Food History website, which sought “to provide culinary enthusiasts and food heritage advocates with data from which they can pursue their own interdisciplinary research into how gastronomy developed in the Philippines and continues to innovate toward contemporary sustainability.”

An early hallmark of authorship was The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes, 1521-1935, published in 2006 by Anvil Publishing. Spanning Spanish colonization to the end of the American insular government, it offered “a rich tapestry of Filipino heritage, showing how daily meals reveal profound historical truths.”

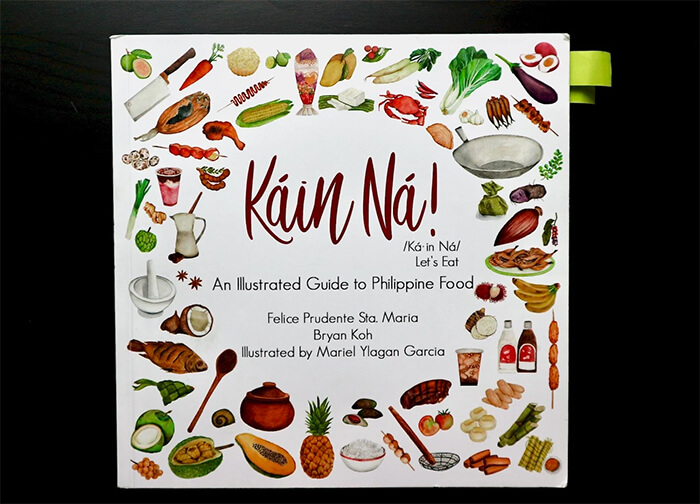

In 2019, Kain Na! An Illustrated Guide to Philippine Food became the first illustrated guide to the subject, co-written by Sta. Maria and Bryan Koh of Singapore, and illustrated by Mariel Ylagan Garcia. Conceived and published by Rajiv Daswani of RPD Publications and supported by Asia Society, the 212-page visual feast showcased a dozen charming chapters from Almusal (breakfast) to Kakanin (rice delicacies) and Sawsawan (dipping sauces).

In 2021, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines published Sta. Maria’s Pigafetta’s Philippine Picnic: Culinary Encounters During the First Circumnavigation, 1519-1522, which served as a retelling of fascinating details of the food and culture described in the chronicler’s journals.

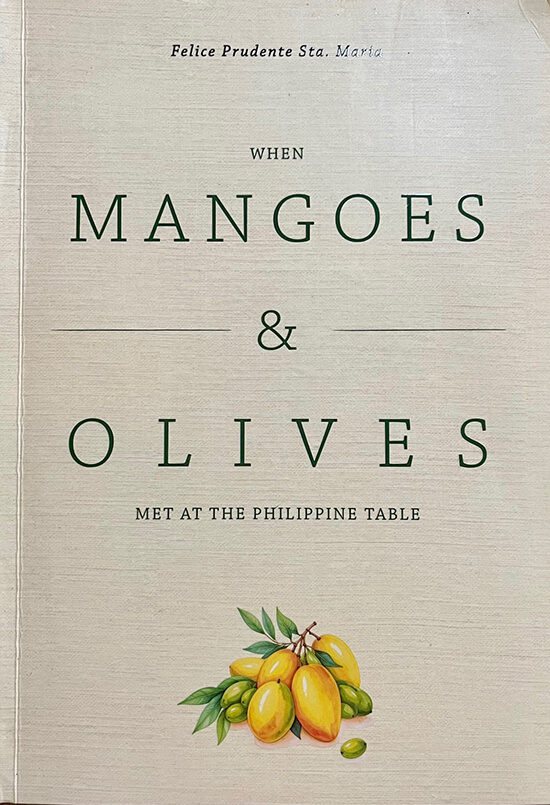

In 2025, the NHCP next published When Mangoes & Olives Met at the Philippine Table. In her Preface, the author describes it as “an account of events based on written materials of varied authors beginning in 1515 (the precolonial times) and ending in 1946 (the year the Philippines gained its independence). The narrative neither claims nor suggests a historical hypothesis. As it goes through nine periods of the country’s history, it reveals how native terroir and tradition dominated culinary expressions during colonial times.”

The nine exhaustive chapters follow a “Preprandial Overview” composed of “Context Behind the Cuisine,” “Sourcing Savor,” “Alimentary Alterations,” and “A Recipe for Research.”

Chapter I starts with “Regional Saviors, 1515-1564.” A principal character is Tomé Pires, “an apothecary from Lisbon who sailed in 1511 with Alfonso de Albuquerque on a Portuguese mission that conquered Malacca…” A decade after Pires started his voyages, Magellan’s chronicler wrote on the first circumnavigation of the world. “Just as Pires had written down details about ports—their safety, provisions, peoples — so did Pigafetta (who) first set foot in Homonhon Island…” He found island food “half cooked and very salty.” He is credited with the “first published reference of Philippine coconut vinegar, coconut and nipa palm wines, and Palawan-distilled rice wine. He documented the first vocabulary of the language spoken in the area, albeit brief, which included culinary terms.” Among these were the Cebuano “Macan” for “to eat,” and “Monoch” for chicken.

The next chapters include titles that correspond to referenced time periods, such as “Food Chains,” “Slow Cooking,” Flavor Blends,” “Blessed Harvest,” “New Fields,” “Food Assessment,” “Defining Moment” (which incorporates the “last decades under Spain” and the “Food Sector During the American Regime”), and wind up with “Table Legacies” by 1946.

A section titled “Postprandial Reflections” bookmarks the narrative before the extensive Annexes that start with “Heirloom Recipes.” It concludes, if preliminarily: “The historical glimpses (in this book) occurred before agribiodiversity, ecoagriculture, food sovereignty, self-governed resources, and even rural poverty became buzzwords. Yet, heritage and food are fundamental in culture—and life for that matter. There is, after all, history in every dish, and a story in every bite.”

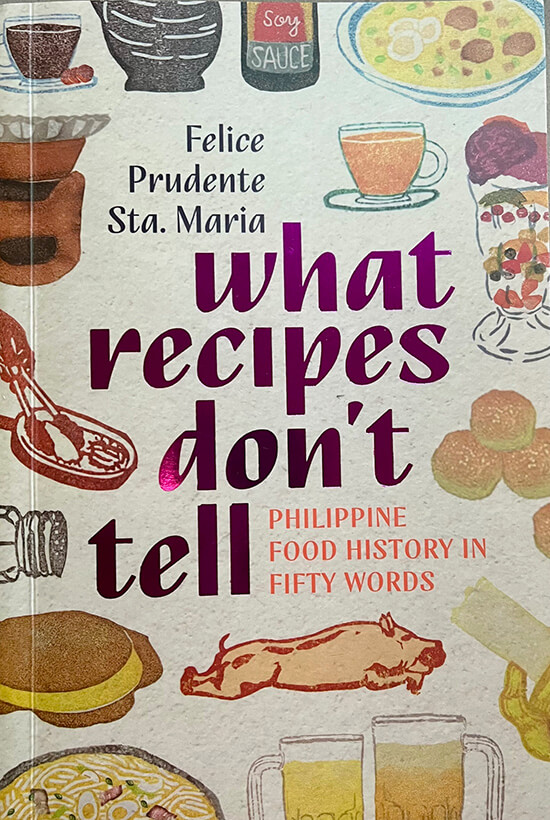

Felice dedicates her most recent book, What Recipes Don’t Tell: Philippine Food History in Fifty Words, published by Bughaw of AdMU Press, to Nick Joaquin. She recollects in her Prologue how a happenstance chat at the CCP in 2007 led her to ask the great writer why he credited “guisado as one of the most important Spanish contributions to Philippine culture.”

Nick acknowledged that he had no documents or records; that it was just his gut feel. In turn, Felice promised to try to prove him right. Nick urged her before they parted, “Let me know what you find.” Unfortunately, as Felice sums it up, “By the time I could safely conclude using written evidence that he was correct, Nick Joaquin had passed away.”

We can still be grateful that Felice pursued her characteristic work of scholarship that now rewards readers with yet another stimulating book on Philippine food history.

On the subject of “Reading Recipes” in her Introduction, she writes: “Enthusiastic interest in the construct of heritage has seen a parallel rise in keenness for vintage and heirloom ethnic cuisines. Deciding what are authentic ancestral foods has raised questions about how to make them and how far back they can really be traced. Antique Philippine cookbooks are increasingly in demand, but they are exceedingly scarce.”

Tireless detective work fuels Sta. Maria’s uncanny explorations through early literature. A back-cover blurb allows: “Uncovered are forgotten, hidden, and ignored details of fifty culinary words foundational in deepening appreciation for native fare: from guisa to kilaw, ensaymada to halohalo, tuba to tsokolate, and linamnam to nayanaya.”

Here’s the entry on guisa: “The hunt by Spanish colonizers to find their comfort foods or something similar in native Philippine cooking included searching for guisado. It is their deeply flavored, richly saucy stews or braised dishes. The root word is guisar, to cook or dress victuals to cure meat. A kindred is guiso, the seasoning of a dish or the sauce of meat or other victuals.”

Felice recounts: “In 1988, National Artist for Literature Nick Joaquin became the first cultural writer to include ‘the introduction of guisado’ as one of twelve greatest events in Philippine history. Each event was ‘epochal’ and ‘by the way we responded to them, determined our response to all subsequent events,’ he wrote in his book, Culture and History.”

Typical of Sta. Maria’s work is the inclusion of diverse reflections that expand the context surrounding inter-related subjects and motifs. Here it’s the inclusion of peripheral yet relevant topics such as on “Who Influence What We Eat” and “Food as Commodity.”

All of 200 pages, it’s a suitable partner to Mangoes & Olives—maybe even a potential sequel in a chain of spiraling explorations that enlighten us on our appetites, past, present, and future.