Maxine Syjuco and the prophets of the brighthouse

Far from the usual stages of Philippine art, the Syjuco Museum is taking shape in Alabang. That distance feels intentional, even if it is not advertised as such. This is not a satellite outpost or a symbolic return. It is simply where the work ended up, after years of friction with a cultural climate that preferred art to arrive already explained.

This was where Cesare and Jean Marie Syjuco withdrew decades ago, after pushing hard enough and long enough to feel the limits of participation. The withdrawal was gradual, shaped by exhaustion rather than drama. The work did not stop. It stopped asking for permission. The BrightHouse, the Syjuco home, became a place where ideas could continue without needing to justify themselves.

What is taking shape now on the family compound is a collection of work that never settled easily into the systems built around it, things always scattered by design now brought together on a scale eight times that of the original Art Lab along Edsa.

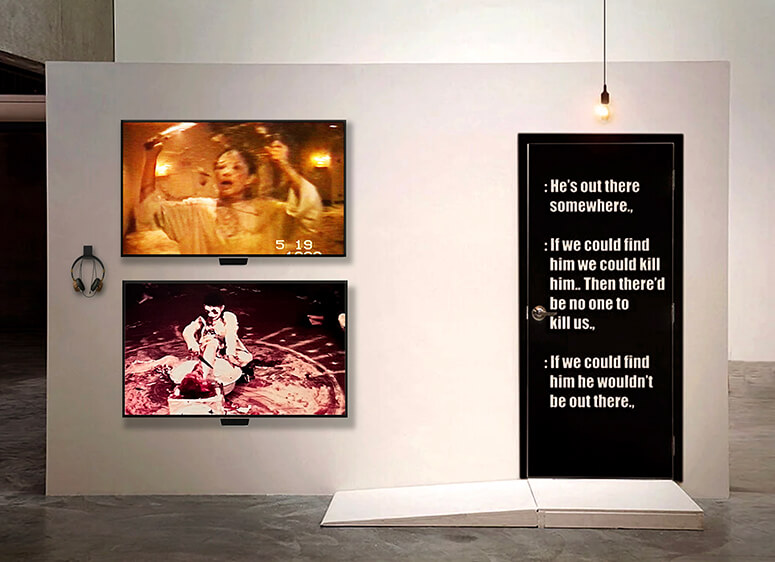

For anyone who paid attention to Manila’s art scene in the 1990s, the Syjucos are not obscure figures. Cesare Syjuco wrote criticism sharp enough to bruise and literature that treated the page as one surface among many. Jean Marie Syjuco worked in performance at a time when the form barely registered locally, forcing her audience to sit with time, the body, and the pressure of the unexplained. Together, they ran Art Lab, a space that functioned less as a gallery than as a pressure chamber for ideas that did not translate neatly into objects or sales.

The task of reopening that history now belongs to their youngest daughter.

Maxine Syjuco was born in 1984 and grew up alongside the work rather than in its shadow. In her telling, art was never something that happened elsewhere. It was not a weekend activity or an intellectual exercise. It was woven into daily life, inseparable from difficulty, argument, and persistence. Money troubles were familiar. Emotional strain was ordinary.

“Depression was a word I understood even before I learned how to spell beautiful,” she says.

![]()

Today, Maxine is both personal assistant and home nurse to her parents. After months of sepsis and complications from diabetes, her father lost his leg to amputation. Recovery has been slow and uneven, marked by phantom pain and a body that no longer cooperates the way it once did. Maxine speaks about care plainly.

“People sometimes ask me why I don’t tire of dedicating my time to my parents, and my answer is simple,” she explains. “Being by their side to take care of them is the very least I can do to show how grateful I am.”

The museum is the architectural extension of that intimacy. It is expansive, but it avoids the trap of being grand. It is dedicated to restoring and holding together more than four decades of work across writing, criticism, performance, and forms that refuse the convenience of tidy labels. Maxine does not describe this as inheritance.

“The Syjuco Museum has been my life-long dream,” she says. “My parents are the light of my world, and I love them with the two greatest traits they have taught me, devotion and passion.” The museum is nonprofit by design. It is not meant to accumulate value. It is meant to circulate attention.

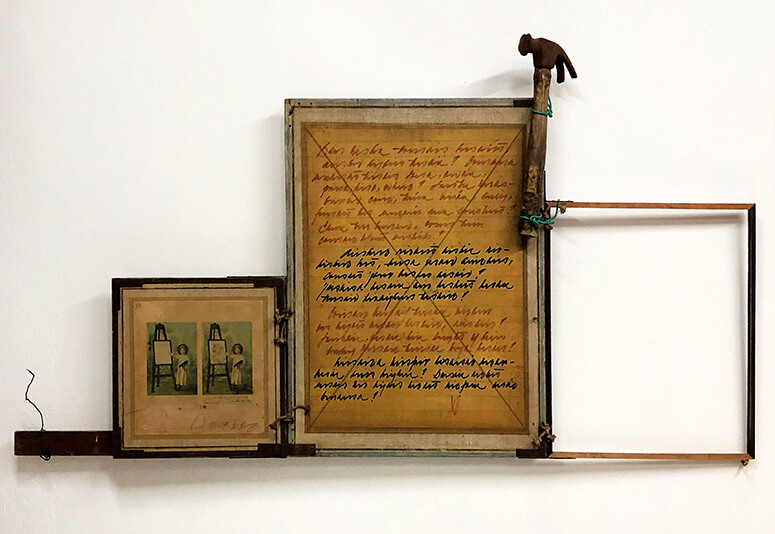

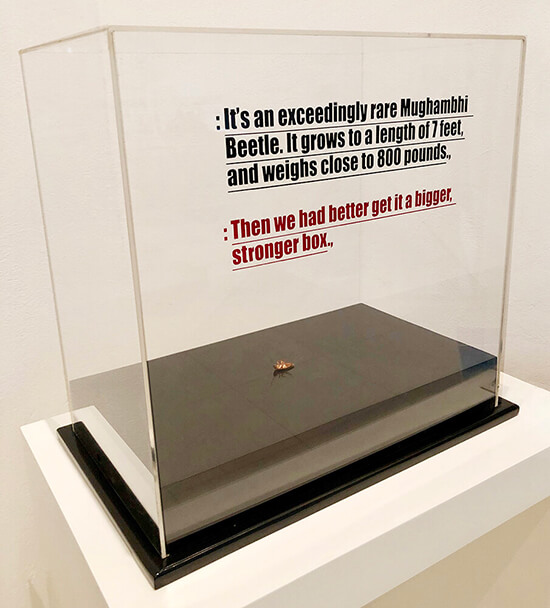

What often unsettles younger audiences encountering the Syjucos today is not difficulty, but timing. Cesare’s experiments anticipated habits of reading that would only become widespread decades later. His “short shorts,” complete narratives compressed into two or three sentences, assumed a reader who could move quickly without losing depth. His “poems for walls,” which he called Literary Hybrids, treated language as spatial and visual, refusing to confine literature to the page.

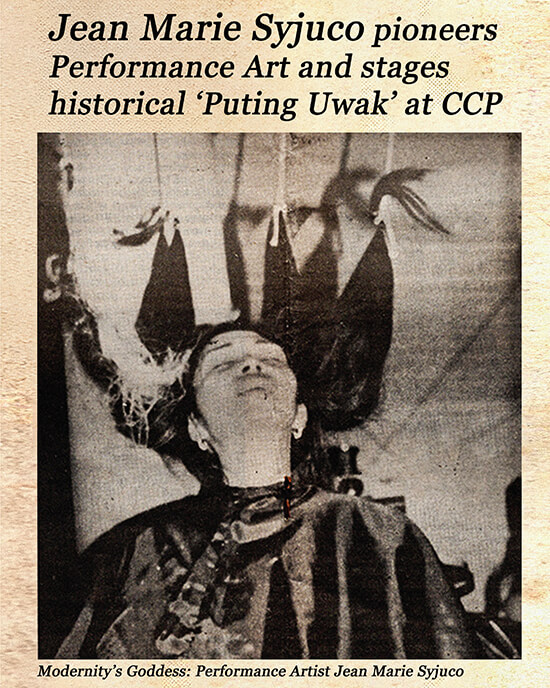

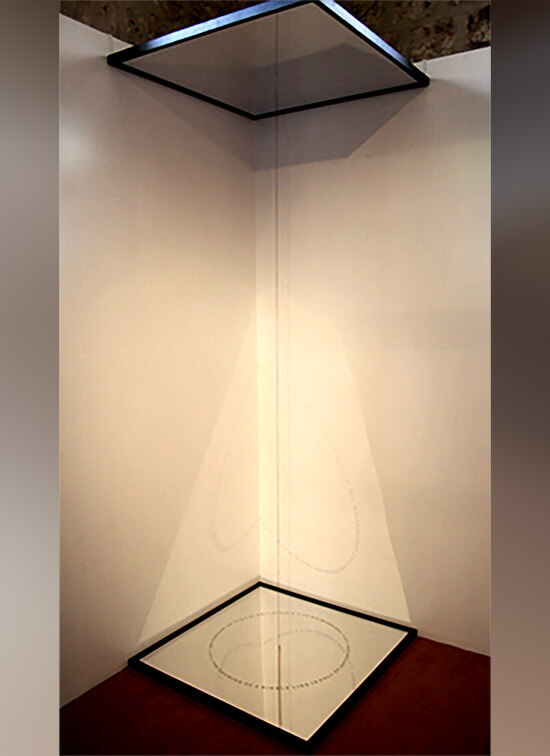

Jean Marie’s work landed with the same refusal to compromise. In a country where performance barely existed as a recognized category, she pursued it anyway, asking audiences to sit with presence, unease, and the weight of time. Her 1992 performance, Puting Uwak, staged at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, remains a reference point. The audience was seated onstage while she occupied the theater seats, upending a hierarchy so familiar it often goes unnoticed. The gesture was simple. Its implications were not.

Maxine resists turning this history into a collection of trophies. The Syjuco Museum is conceived as a living space because the work itself refuses to settle.

“I am hellbent on reminding the world, particularly our fellow Filipinos, of the undeniable ingenuity and brilliance that our country possesses,” she says. Her insistence is aimed less outward than inward, toward a local habit of narrowing what Filipino art is allowed to look like.

“What people fail to realize is that the beauty of Filipino art lies in its vast cultural diversity. One does not need to paint coconut trees or scenes of the marginalized in order to be purely Filipino.”

Preservation, in this house, is not a neutral act. When Art Lab first opened in 1990, Cesare described it as a space for promoting energy rather than objects. Maxine returns to that idea often.

“Art, after all, is energy, and scientifically, energy never dies. It simply changes form,” she says. Restoration becomes an act of translation. It is a way of allowing work shaped by a specific, volatile moment to remain legible without being embalmed.

Memory sharpens the stakes. At the height of his career as a critic, Cesare wrote relentlessly, sometimes five to seven articles a week. His influence was substantial, and so was the resentment it provoked. Death threats followed, serious enough to alter daily routines. Maxine recalls this without drama, as evidence of how writing, performance, and criticism have long been treated as disturbances rather than contributions.

That hierarchy remains largely intact. Painting and object-based work continue to dominate the conversation because they are easier to house, to insure, and to sell. Performance, poetry, and criticism leave less behind. What they produce instead are questions, arguments, and aftereffects.

Legacy, as Maxine understands it, is not something to be protected from touch. It is something to be engaged with. She does not ask future artists to be reverent. She asks them to recognize persistence. “Art, to me, is about letting your insides come out,” she says. The proposition is direct and not especially comforting.

Success, for her, stays close to home. It looks like joy for her parents. It looks like pride shared rather than claimed. It looks like placing Philippine avant-garde practice within a longer history of refusal and devotion, one that values interior necessity over approval.

“What it all boils down to is love,” Maxine says. “Love for my parents, love for art, and love for our country.”

* * *

The Syjuco Museum is located at the Syjuco Compound, 325 to 327 Country Club Drive, Ayala Alabang Village, Muntinlupa.